![]()

Volume 7, No. 3

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

Browse the archive |

|

|

|

|

By Ethan Nedeau

An article I wrote that appeared in the “Science Insights” column of the Gulf of Maine Times’ summer issue examined the natural history and plight of alewife populations. Several readers have since inquired about current conservation and management issues for alewife. Allow me to elaborate on a few of those concerns:

Angler misperceptions

|

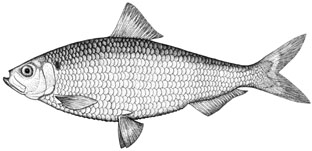

| Alewife illustration © Ethan Nedeau |

Scientific studies have not shown that anadromous alewife negatively influence bass; any such claims are hearsay and myth. Adult anadromous alewives do not feed while in freshwater, and juveniles eat zooplankton, tiny crustaceans, and insect larvae. Several studies have shown that juvenile alewives are important forage for bass and other predators, and scientific evidence suggests that alewives promote healthy bass fisheries.

Water conservation and management

In small coastal rivers and streams, water levels affect a fish’s ability to migrate upstream and downstream. Too little water during critical migration or spawning periods can disrupt a year’s worth of reproductive effort. Low water levels decrease passage efficiency at dams; reduce access to, and the amount of, habitat; delay or prevent migration; and increase mortality because of fishing, predation or unsuitable environmental conditions.

Low-flow periods are increasingly common in coastal streams and rivers because of groundwater withdrawal for domestic, industrial and agricultural purposes. Some rivers, such as the Ipswich River in eastern Massachusetts, become dewatered during dry summers. Climate change is likely to result in warmer and drier summers in the Northeast, and this will exacerbate water shortage problems. Lack of winter snowfall and heavy spring rains may cause low-flow periods in early spring, which may prevent alewife runs in streams and small rivers. A summer and fall drought may prevent juveniles from migrating to the ocean.

Water levels in regulated rivers are managed for multiple stakeholders, such as power companies, waterfront property owners, and recreational users. It would be beneficial to include anadromous fish among the stakeholders, and to manage flows to meet the needs of these fish during critical spawning or migration periods.

Upstream fish passage

Ancestral spawning areas for shad, herring, salmon and sturgeon remain inaccessible because of dams without fishways. In addition, fishways do not always work—different species have different abilities to ascend fishways, and often only a fraction of migrating fish can pass. Many fishways in the Northeast were designed for salmon—a leaping fish—often leaving sturgeon and alewife with nearly insurmountable obstacles.

Downstream fish passage

Dams should provide upstream AND downstream passage! Most fishways are designed to get fish over dams on their way upstream. Ocean-bound fish usually must swim through turbines, where ten to 80 percent of the fish are killed. Dams also slow downstream migration, causing fish to congregate at unnaturally high densities above dams, leading to high mortality.

Ethan Nedeau is a science translator for the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. He can be reached at ejnedeau@attbi.com.