Printer

friendly format

Click

on the picture to enlarge |

|

Goodbye

to the ice pond of old?

What

the thawing and freezing of lakes can tell us about climate change

By

Ethan Nedeau

In

these days of increasing societal demands on our time, we are becoming

more and more detached from Earth's natural calendar that once guided

us. Some people are still in tune with subtle seasonal changes,

but most of us are too distracted—we blink and winter turns

to summer; we blink again and the maple leaves are turning red.

While growing up on a lake, I marked time based on where and what

fish I could catch, the appearance of water lily blossoms, the congregation

of cormorants in the river, or the “rum-rum-rum” of breeding

bullfrogs. When alder leaves were the size of a mouse’s ear,

it was time to fish for brook trout. Spotted salamanders could be

found crossing our wooded paths on the first warm rainy night after

the spring snowmelt, and this meant that we could soon plant peas.

Some

of my fondest memories of growing up near a lake are of watching

the freeze and thaw of the ice. A lake does not go quietly when

it succumbs to the cold—its protests are like sharp thunderclaps

that reverberate across the skies and through the forests, or like

an oak bent to its breaking point before it finally splinters. I

used to lie in bed listening to the lake make ice, and wiggle my

toes with thoughts of skating in the morning. My grandfather used

to skate by Thanksgiving, but nowadays, my family feels blessed

if we can skate by Christmas. A few years ago, the lake was still

unfrozen in late January, and three years ago, two local fishing

derbies were cancelled in February—for the first time ever—because

of thin ice.

|

People

have been recording so-called ice-out dates on lakes for well over a century,

providing insight into long-term trends in ice duration (the time between

freezing and thawing of lake ice), which can indicate climate trends.

Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey in Maine examined 64 to 163 years

of ice-out data for 29 New England lakes. They found that average ice-out

dates are now nine days earlier in northern/mountainous regions, and 16

days earlier in southern New England. Coupled with anecdotal observations

of later freeze dates in the fall, average ice duration may have declined

by over a month in some areas in New England over the last century. The

scientists used the ice-out data to infer an average late winter and early

spring temperature increase of 1.5 ºC (2.7 ºF) since 1850. There

is similar evidence from elsewhere in North America:

- Between

1969 to 1988, average ice duration became 20 days shorter on an Ontario

lake, mostly accounted for by earlier ice-out dates.

- Average

ice-out dates became 15 days earlier from 1890-1991 on a Wisconsin lake,

and the years 1980-1991 accounted for eight of those days.

- Between

the 1950s-1990s, average ice-out became seven days earlier in six central

and western Canadian lakes.

- Between

1846-1996, in lakes and rivers in the northern hemisphere, freeze dates

became 5.8 days/100 years later and ice-out dates became 6.5 days/100

years earlier.

These

studies all suggest that springtime is arriving sooner and may mean that

some lakes are becoming warmer. Ice-out, however, is not the only sign

of spring that is arriving sooner—studies show numerous examples

of plants and animals responding to warmer springs. In the latter half

of the 20th Century, dates of the last hard frost and lilac blooming have

both become significantly earlier in New England. Scientists in Wisconsin

studied 55 springtime events—from the appearance of pussywillows

to robins to trillium blooms—and found that for all combined, these

events occurred an average of 0.12 days earlier per year over 61 years

(7.3 days). From one year to the next, 0.12 days might not seem important.

But what is important is that over the long term, the changes are consistent

and headed in one direction. The climate is changing—and plants,

animals and ecosystems are responding.

|

The

Gulf of Maine:

Warming inland, cooling offshore?

Scientists

predict a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide over pre-Industrial

levels by 2100 caused by combustion of fossil fuels and biomass

burning. Climate change models indicate that over the next hundred

years Earth’s temperatures will increase by 1.4 to 5.8 ºC

(2.5 to 10.4 ºF) from 1990 levels.

Wintertime

temperatures in northern latitudes are expected to show the greatest

warming. Between 1895 to 1999, average temperatures for the New

England region (including northern New York) increased by 0.41

ºC (0.74 ºF), though some subregions showed higher increases

of 1.0 ºC (1.8 ºF) in New Hampshire and 1.28 ºC

(2.3 ºF) in Rhode Island. The coastal zone warmed by 0.94

ºC (1.7 ºF). Wintertime temperatures increased by an

average of 1.0 ºC (1.8 ºF) over the same period, including

a 1.94 ºC (3.5 ºF) increase in New Hampshire and 1.67

ºC (3.0 ºF) increases in Rhode Island and Vermont.

Despite a long-term trend toward a warmer climate, the Gulf of

Maine region might actually experience a period of cooling in

coming decades. Scientists believe that the Gulf Stream—which

carries warm water northward from the tropics—might weaken

or shift its course due to melting of arctic sea ice, possibly

leading to a rapid cooling period with longer and harsher winters,

similar or perhaps far more severe than the 2002/2003 winter in

our region.

|

|

Ice

duration data for North American lakes is just the tip of the iceberg

for compelling evidence of climate change. There is now an unprecedented

melting of glaciers throughout the world, particularly in polar regions.

Arctic permafrost is thawing and the Arctic growing season has gotten

significantly longer. Russian rivers are discharging much more freshwater

and threaten to upset global ocean circulation patterns. Arctic sea

ice is melting fast—both in spatial extent and depth. Some models

predict that the Northwest Passage will be ice-free in the summer

within 75 years.

Fish habitat disruptions

Why is it important that ice duration on local lakes is decreasing?

What does this mean for natural ecosystems? The main concern is not

ice duration per se, but that lakes may be getting warmer. In northeastern

lakes, climate change is expected to cause a decrease of cold-water

habitats, increase of warm-water habitats, reductions in dissolved

oxygen, reduced lake levels, changes in lake mixing regimes and altered

nutrient cycles. This will affect nearly everything about our lakes—habitats,

populations, communities and ecosystem processes. These types of effects

will also be evident in streams and rivers.

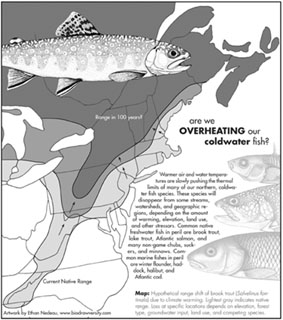

Using

climate change models, scientists predicted changes in lake fish

habitat throughout North America based on anticipated effects on

temperature and dissolved oxygen. They predicted a 45 percent loss

in cold-water habitat, with virtual disappearance of such habitats

from many shallow and medium-depth lakes. Native brook trout, blueback

trout, lake trout and salmon will lose habitat because of climate

change, as will non-native (but recreationally important) rainbow

trout and brown trout. Many non-game species that are ecologically

important—such as dace, chub, darters and sculpin—will

also lose habitat as waters warm.

Scientists

predict that warm-water habitats will increase, causing the “good

growth period” of warm-water fishes to become several weeks

longer. Warm-water fish, such as smallmouth bass, largemouth bass

and bluegill—will likely expand their habitats as previously

cool habitats become more suitable. In the Northeast, most of these

warm-water fish are also non-native predators. Their competitive

advantage over native species will increase as water temperatures

rise.

|

Is warmer better?

When the woodpile is rapidly dwindling by early March, or wind-driven snow

makes for a harrowing commute home, we are all tempted to think fondly of

climate change. What are a few extra degrees? People might be more alarmed

if we were facing “global cooling.” Only 20,000 years ago, average

global temperatures were 6 to 7 ºC (10 to 12 ºF) colder than they

are now, and most of our region was covered with glaciers up to two miles

thick. Native plants and animals were forced into refugia far out on the

continental shelf or to the south. We are now facing the prospect of a warming

period of nearly the same magnitude—except much faster—and the

effects will be equally dramatic. The ten hottest years of the last millennium

have all occurred since 1983. If Boston's average annual temperature were

to increase by 5.6 ºC (10 ºF), its climate would be similar to

that of Atlanta, Georgia. In Nova Scotia, if Halifax's average annual temperature

were to increase by the same amount, its climate would be similar to that

of Philadelphia.

Perhaps in 100 years April will no longer signify wood frogs and spotted

salamanders, June may no longer signify brook trout rising for caddisflies,

July may no longer signify fireflies and painted turtles and January may

no longer signify ice skating and snow angels. Climate change threatens

everything about the nature of New England and eastern Canada—the seasons

that shape our lives, the woods and waters that have sustained us for centuries,

and our cultural and economic prosperity. Whether we bicycle to work, or

encourage our political leaders to support regional and global initiatives,

it is important that we do all we can to address this global problem.

Ethan Nedeau is a science translator for the Gulf of Maine Council. He

can be reached at ejnedeau@comcast.net.

. ©

2004 The Gulf of Maine Times |