Do salt marshes serve as fish nurseries?

Do salt marshes serve as fish nurseries?

Delving beyond the sound bite

Printer Friendly Page

By Peter H. Taylor

THERE'S NO QUESTION that salt marshes are incredibly rich, productive and valuable parts of the Gulf

of Maine ecosystem. They contribute copious amounts of vegetation to the food web. They help to

filter pollutants from the water. They provide habitat for numerous species of fish, birds and

invertebrates. They are beautiful places to paddle a canoe, watch birds or go fishing. For these

reasons and more, salt marshes deserve protection and restoration.

But whenever ecologically minded people talk about salt marshes, it’s almost a sure bet that

the word “nursery” will get tossed in. The dogma is that some species of marine fish call salt

marshes home when they are young, before they move offshore and are caught as adults. Indeed,

the notion of salt marshes as fish nurseries has become “common knowledge” among resource managers,

conservationists, environmental educators, and many laypeople. Usually it’s treated as a basic

tenet of coastal ecology in public outreach materials, educational programs, magazine articles,

and non-scientific books and people routinely cite this nursery role to help justify protecting

and restoring salt marshes. Based on common knowledge, one might assume that Gulf of Maine salt

marshes virtually teem with juvenile haddock, cod and other commercially important fish and that

destroying a salt marsh would be like destroying a hospital nursery.

Although salt marshes intuitively seem like good nursery habitats, I hadn't heard much direct

scientific evidence for the idea, particularly in the Gulf of Maine. Is it true that marine fish

use salt marshes as nurseries? Which species? Do young fish rely on the marshes, or just

occasionally happen to be found there?

Recently I dug into the scientific literature to find out. Clearly, salt marshes support

commercial and recreational fisheries, and overall ecosystem health, by contributing to the

food web and improving water quality. But the question of salt marshes as fish nurseries is an

unresolved, thriving area of basic and applied research. I learned that the evidence for the

nursery role is patchier and the whole story more complex than one might expect. “Salt marshes

are nurseries” really is just a sound bite that masks key facets of the subject. That's OK. Often

the best way to communicate is to boil complexities into a form that is quickly digestible by the

majority. However, an accurate understanding of habitat functions and linkages is essential for

ecosystem-based management. Resource managers and other coastal decision-makers around the Gulf of

Maine need more than the sound bite.

1. What does “nursery” really mean?

Often people declare a salt marsh or other habitat as a nursery simply because young fish are

present. That's not sufficient. A working group at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and

Synthesis recently focused on clarifying the definition: To qualify as a nursery, a habitat must

contribute a disproportionate number of juveniles into the adult population. In other words, more

young reach adulthood from that habitat, acre for acre, than from other habitats. The

disproportionate contribution can arise due to any combination of these four factors in the nursery

habitat: (1) more young per unit area, (2) faster growth, (3) higher survival, and/or (4) better

success moving from nursery to adult habitat. Many studies purporting to examine the nursery role

of salt marshes don't look at these factors, making it impossible to discern the nursery value.

I'm not aware of any studies from the Gulf of Maine that provide this information.

2. Nursery value differs among sites

Tom Minello of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Fisheries Service

laboratory in Galveston, Texas, and colleagues analyzed more than two dozen studies on the

abundance, growth, and survival of fish and free-swimming invertebrates in salt marshes around

the world. They found that the nursery value of these habitats varies among and within geographic

regions. For example, salt marshes seem to play a greater nursery role in the Gulf of Mexico than

along the southeastern U.S. Atlantic coast. The study also suggested that, within geographic

regions, the nursery value of a salt marsh is influenced by its orientation along the coast,

current patterns, tidal flushing, and proximity to other habitats such as seagrass beds. Because

rigorous studies of nursery functions are scarce, Minello's analysis did not include any data

from the Gulf of Maine. However, the findings hint that (a) it's impossible to infer the nursery

significance of salt marshes in the Gulf of Maine from studies in other regions, and (b) marshes

around the Gulf of Maine probably vary in nursery value.

3. “Nurseries'” economic impact is unknown

Sometimes non-scientific authors attempt to place dollar values on the nursery role of salt

marshes something like, “One third of fished species depend on salt marshes as nurseries, and

commercial fisheries are worth $300 million per year. That means salt marshes are worth $100

million annually as fish nurseries.” This type of conjecture goes well beyond what's actually

known. Although more than a dozen species of marine and estuarine fish are known to occur in

the Gulf of Maine's salt marshes, scientific data do not yet answer the question of how many

species caught offshore actually use and rely on salt marshes as nurseries. Even if a species is

found in salt marshes, other young fish of the same species might live in non-salt marsh habitats,

and the salt marshes may or may not truly function as nurseries, as discussed in section 1 above.

It is premature to put a dollar figure on the economic value of Gulf of Maine salt marshes as

nurseries for commercially important fish.

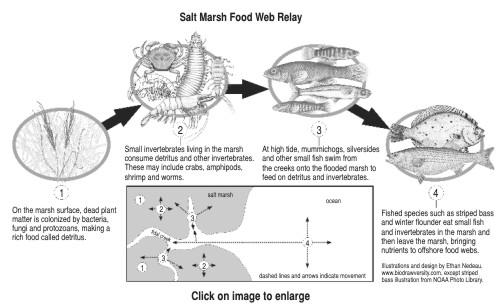

4. Salt marshes and the “food web relay”

Often the “nursery” idea gets top billing, but salt marshes perform many other valuable

functions in the ecosystem. One way that they benefit fisheries is through the food web. Few

animals eat salt marsh plants, but after the plants die they become colonized by bacteria,

fungi and protozoans, making a rich food called detritus. Detritus is the initial step in

a “food-web relay” that ultimately feeds commercially important species. First worms, crabs

and other invertebrates eat the detritus on the marsh surface. At high tide, mummichogs,

silversides and other small fish swim across the flooded marsh surface to feed on the detritus

and invertebrates. At low tide, the small fish retreat into deeper creeks. Larger fish such as

winter flounder and striped bass venture into the creeks and feed on the small fish. In turn,

the larger fish swim out of the marsh, which connects the salt marsh's food web with that of

the coastal waters beyond. Through the food-web relay and the export of nutrients, salt marshes

help to sustain commercial and recreational fisheries.

5. Other habitats act as nurseries

Salt marshes are widely discussed as nursery habitats, but it is less recognized that other

shallow-water habitats in the Gulf of Maine may also serve as nurseries. For example, eelgrass

and kelp beds host young-of-the-year Atlantic cod, mussel beds and cobble bottoms offer young

sea urchins a refuge from predators, and rockweed habitats along rocky shores are used by

juveniles of many species, including herring, pollock and winter flounder. These other habitats

might help to sustain fisheries, and they should be kept in mind for habitat conservation and

restoration.

Let's step back and look at the big picture again. The lack of scientific evidence doesn't

mean that salt marshes in the Gulf of Maine aren't fish nurseries. We simply can't say yet.

Nor does it mean that salt marshes shouldn't be protected and restored. There are plenty of

reasons to retain that priority, aside from the nursery function. Nor should incomplete

scientific knowledge deter progress with ecosystem-based management in the Gulf of Maine.

Knowledge is never complete, the precautionary principle prescribes protection even if

cause-and-effect are not scientifically proven, and adaptive management can take into account

the emerging understanding of salt marshes and other habitats.

What about all those outreach and education publications for students and non-scientists?

My suggestion is to revise the sound bite: “Scientists postulate that salt marshes act as

nurseries for some fish species.” I think it has the same impact and it's accurate.

Peter H. Taylor is a consultant for the Gulf of Maine Council's Science Translation Project.

For information visit:

www.gulfofmaine.org/science_translation.

Contact Peter at: peter@waterviewconsulting.com