Gulf Voices: Governor of growth

Printer Friendly Page

By Dave Kellam

|

PHOTO: COURTESY DAVE KELLAM |

When the first steam engines were invented in the early 18th century, they were wondrous machines that could do tremendous amounts of work. The only problem was that they often blew up.

But in 1787 inventor James Watt created a better steam engine. One of the improvements was a simple device used in wind mills to prevent them from flying apart in wind storms. The revolutionary concept Watt gave to the world of engineering was the integration of a self-regulating device into an engine so it would not require constant human monitoring. He freed people to concentrate on their work instead of their machines.

Fast forward 220 years. Today the ancestors of the steam engine have enabled humans to concentrate on building cities and industries, changing the landscape faster than any time in history. Land can now be cleared, paved, and built upon in a matter of days rather than years. Like water rushing from flood gates, agriculture and urban development has sprawled across the United States at an astonishing rate since Watt's improvements ignited the industrial revolution.

The cost of expansion

Centuries of building and expansion has come at a cost, namely in the degradation of our environment and specifically our water resources. The construction of impervious surfaces such as roads, buildings, and parking lots prevents water from infiltrating into the ground and recharging aquifers. Impervious surfaces also concentrate contaminants, which are washed downstream during rain or snow-melting events, thus polluting waterways. Studies by the Center for Watershed Protection have demonstrated water quality deterioration occurs where impervious surfaces cover greater than 10 percent of the watershed area. Recent work by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection suggests that in the northeastern United States, the percentage of impervious surface cover that begins to impact water quality could be closer to seven percent. In 2005, a study by the New Hampshire Coastal Program and the U.S. Geological Survey demonstrated that the percent of urban land use in stream buffer zones and the percent of impervious surface in a watershed can be used as indicators of stream quality.

Several coastal watersheds that drain into the Gulf of Maine are at or approaching the 10 percent level of impervious surface coverage. According to the Casco Bay Estuary Partnership's 2005 State of the Bay Report, impervious surfaces cover approximately 5.9 percent of the entire Casco Bay watershed. However, levels greater than 10 percent occur in nearly all subwatersheds closest to the coast. According to the 2006 State of the Estuaries Report from the New Hampshire Estuaries Project, the area of impervious surfaces in New Hampshire's coastal watershed has grown from 24,349 acres (9.7 hectares), or 4.7 percent of the total land area in 1990, to 41,784 acres (16.6 hectares), or 8.0 percent of the total land area in 2005.The number of the 37 subwatersheds with greater than 10 percent impervious surface cover was two in 1990 and 10 in 2005.

|

COURTESY: NATURAL LANDS TRUST |

|

The New Hampshire report also documented an increase in sprawl-type development, defined as the average imperviousness per capita. Overall, the average imperviousness per capita for the 42 municipalities of the New Hampshire coastal watershed grew from 0.152 acres (0.06 hectares) per person in 1990 to 0.217 acres (0.09 hectares) per person in 2005. While the average values indicate an overall trend in sprawl-type growth, analysis reveals that smaller towns with abundant undeveloped land are experiencing far greater increases in land consumption per person than the larger communities that are closer to reaching buildout.

So the areas most susceptible to sprawl are communities with relatively large tracts of land available for development. To solve the problem of sprawling growth, we should channel the spirit of James Watt and apply his revolutionary engineering concept to land-use planning. Metaphorically, we need a “device” that will relieve development pressure when the development engine picks up speed. It must be designed to avoid catastrophic failure of the machine, in this case the ecology of the region, by automatically offsetting the impacts of sprawling development.

Conservation subdivision ordinance

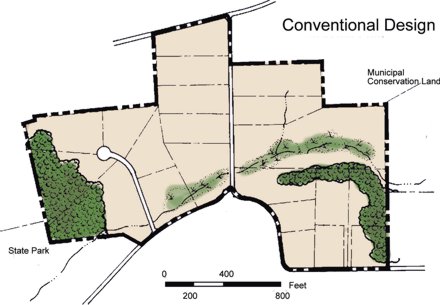

I believe the device we are looking for is the conservation subdivision ordinance. Also called an open space ordinance, this type of land-use regulation allows a land developer to cluster development in a land parcel away from critical natural resources. The remaining land must be permanently protected from further development, usually with a conservation easement. A mandated balancing act can ensure that new development will be offset with protected open space. The result is a landscape of well-planned communities and protected open space.

This “growth governor,” however, is not completely automatic. Local land-use boards must actively work with developers to conserve areas that will create contiguous habitat blocks across communities and protect critical water resources of the region. Furthermore, developers must conserve truly buildable land, not simply a wetland on the property that is already protected. A good approach to mesh conservation subdivision ordinances with other land-planning tools, such as target conservation land inventories and community development density targets, is the conservation overlay district. This concept helps achieve land protection on a watershed scale that will better maintain the ecological functions.

It is important to note that conservation of land benefits many natural resource services in addition to water quality. According to the 2005 report, Managing Growth: The Impact of Conservation and Development on Property Taxes in New Hampshire, by the Trust for Public Land, "conservation often enables the continuing viability of working farms and forests which maintains the rural community, contributes significantly to the town's economy and employment, and may help to stabilize tax rates that threaten affordability of home ownership for the average family. Land conservation can be used as a tool in both protecting resources that contribute to quality of life (from drinking water protection to scenic beauty and recreation), as well as to help guide the path and location of municipal growth to those areas that are most appropriate and that are most cost-effective for towns to service."

I believe that if James Watt were alive today, he would be a strong advocate for conservation developments. Even though he was one of the key contributors to the industrial revolution, he also understood how important it is to govern growth.

Dave Kellam is project coordinator for the New Hampshire Estuaries Project in Durham, New Hampshire. He can be reached at dave.kellam@unh.edu.

© 2007 The Gulf of Maine Times