Travelogue

Sandbar Social: Cape Cod’s wet and wild residents

By Karen Finogle

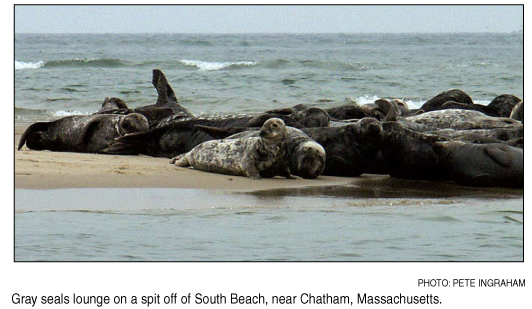

A writhing mound of flesh filled both lenses of my binoculars as I trained them on a sandbar just off shore. Dozens of bodies lay in thick, uneven rows, occupying every last grain of earth and spilling into the cool, shallow water of the Atlantic. Some let their heads droop, resting them on the ground or on neighboring flesh. Others held their thick necks erect, their shoulders pulled up into a half-sitting stance to focus dark eyes in my direction.

I panned my binoculars left, then right, back again, following the borders of the small spit of land on which these beachgoers were settled. It was an island drained of any distinct color. A palette of mottled grays, browns and blacks blended in a massive sea of seal blubber that rose and fell with the shifting and settling of bodies.

We had heard the low, undulating rumble of their voices before we saw them. The summer air was thick, draped in a vaporous veil the sun, sequestered by rain clouds, had not yet lifted. My partner Pete and I had decided to walk South Beach, in Chatham, Massachusetts, anyway. There was only a slight breeze, and the undeveloped, often uncrowded Cape Cod beach, a spigot of sand and grassy knolls that ended only at the southern shores of Monomoy Island, was too alluring to pass up.

Kicking our shoes off at the bottom of the stairs to Chatham Light Beach, Pete and I sunk our feet into the cold sand and turned right, walking by Chatham Harbor towards South Beach and the open sea and passing only a few others who had ventured out on this overcast Sunday morning. As we walked, the din of the gray seals became audible: a crescendo of guttural barking and hooting as we crested a small slope of sand. I wondered at the origin of the sound, what could be drowning out the more melodic and familiar push and pull of the tide. I wondered until we rounded a bend where South Beach proper began.

On a sandbar unearthed by low tide and just a short wade from where we stood, a hundred or more gray seals had hauled out to rest, something, I learned later, these semi-aquatic animals do daily. It was a new phenomenon for me, a native New Hampshirite born among granite peaks whose state’s diminutive coastline had never produced such a colossal gathering of pinnipeds.

Even Pete, who had spent summers since childhood visiting the Cape, seemed transfixed by the spectacle. We traded binoculars back and forth, watching the mammalian drama unfold. Most of the gray seals on the spit kept their front flippers tucked neatly against their stomachs, with eyes squinted shut against the daylight. Their splayed, torpedo-like bodies looked awkward and alien on land.

A few seals lounged in what looked like a yoga pose; their hind flippers held high in the air, heads lifted slightly off the ground. Were they the smaller females or juvenile males wary of being rolled upon by one of the larger adult males, which might weigh in at 1,000 pounds (more than 453 kilograms) and measure eight feet long (almost 2.5 meters)?

A handful of the seals stayed in the water; their heads like fishing bobbers floating on the surface and always pointed in our direction—a deployed flotilla of Navy men, I imagined, ready to sound an alarm or mount a defense.

The last official count of gray seals in the Chatham area took place in 1999 when biologists estimated there were 5,600 animals; the number has likely increased to about 6,000. While most Chatham residents have become accustomed to their saltwater neighbors, seeing even one gray seal 30 years ago would have elicited a mouth-agape response, not unlike my own, from almost every other veteran seaside dweller and marine biologist alike.

Hunted for bounty until the 1960s, gray seals were considered extinct in the waters off New England until they received protection, first from Massachusetts in 1965 and then by the federal government in 1972 under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which prohibits the killing or harassment of any marine mammals. Over time, seals from a large refuge colony on Sable Island, off Nova Scotia, migrated and re-colonized Massachusetts. With the Cape’s abundance of sand eel, a favorite staple, and fish, skates and squid, breeding and pupping on Muskeget Island in Nantucket Sound began. In the late 1970s, less than 20 seals were counted in those waters, but by 1994, because of migration and successful pupping, 2,010 seals were reported.

As sunlight began to burn through the cloud-ceiling overhead, Pete and I broke from our vigil and continued down South Beach. I was reluctant to leave the sovereign island nation of Halichoerus grypus, the “hook-nosed sea pigs,” but the firm sand at the water’s edge and the skipping rocks, worn thin and smooth, puckering in that wet cement surface lured us away. So too did the wide expanse of nothingness—the light surf breaking on an empty beach that extended towards the horizon, populated only by busybody terns, gulls and plovers.

We wandered aimlessly; the seal raucous faded on the breeze that whispered by us. For awhile, Pete and I beach combed for shells, stopping to pick different ones up and studying the rich purple, green and blue hues before dropping them back on the sand. I like to imagine the beach as an art gallery. Exhibits change twice daily by tidal curators, where everything is on loan from the sea.

We were a mile, maybe two, past the seal colony when, looking back out at the ocean, I spotted one, then another dark gray head bobbing in the breakers near a smaller sandbar. Our aquatic equivalents didn’t haul out but dove and surfaced in the shallow waters, close enough that without binoculars I could study their antics, which always suggested fun.

It seemed that these two clowns were intent to locate and study us as well. Their heads always pivoted towards shore, like periscopes, when they sought a breath of air, as if tracking our movements. Were they curious about their distant cousins who had, for unfathomable reasons, abandoned water for a life on land? Did they puzzle at our awkward, erect appearance? Or, as fishermen, did they view us merely as competition for the slippery morsels they chased beneath the water’s surface?

In recent years, some of Cape Cod’s fishermen have recast the gray seal in the role of unsavory competitor, one that gorges itself on commercial fish stock like cod, haddock and flounder. No conclusive proof exists yet to indicate the robust seal population has a negative effect on the industry. Surely overfishing and environmental conditions are also at play, argue marine biologists. Probably so, but stories of empty fishing weirs and below-average catches still permeate the region. No one has advocated harming the seals, but their sandbar socials must be an eyesore for those whose nets ply the same waters.

But not, it turns out, for the small crowd that had gathered near the island colony by the time Pete and I walked back up South Beach. The sun had emerged, a luminescent pied piper calling forth the masses. And the tide had slipped farther out, narrowing the channel of water between shore and sandbar. A group of 15, maybe 20, people had gathered near the seals, and some had waded out in the shallow water, cameras in hand, not more than 20 or 30 feet (six to nine meters) from the bobbing sentinels.

“They’re going to get bitten,” I whispered to Pete. He nodded. I wanted to usher these well-intentioned people back. To penetrate the seals’ world in such a manner, without invitation, seemed wrong, even to this pinniped neophyte. Later, after reading a brochure from the Cape Cod Stranding Network on seal watching guidelines, I learned that the crowd should have stood at least 150 feet (almost 46 meters) from the resting seals. And that the intent gaze that more and more seals drew upon us, the greater number of heads that had lifted from the sand and were cocked in our direction, had not been signs of mutual curiosity but ones of harassment. We bipeds, especially the ones who wandered too close, had impeded on the seals’ much needed cycle of rest.

Pete and I didn’t stay long. There is always a little magic lost when your discoveries become everybody else’s. It’s as if the wildness of the moment became diluted as more feet waded closer and closer to the seal colony. That is nature’s hold on us. In revealing herself, she draws us to her—pulling at our primitive core until we are compelled to become part of her. Many feet in the water, unsure of how far to wade.

Karen Finogle, a free-lance writer and senior editor at AMC Outdoors, lives in Durham, New Hampshire.

[ back to top ]

|