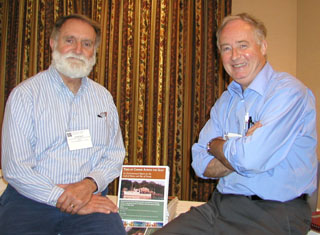

Gerald Pesch (on left) and Peter Wells

Photo: Andi Rierden

|

|

Q & A:

Gerald Pesch and Peter Wells

Tides of change, for better or worse?

By Andi Rierden, Editor

While the Gulf of Maine is considered generally healthy, coastal development, contaminants and declining fish stocks have made historic changes in its overall quality, according to the editors of a new report released last month at the Gulf of Maine Summit. Tides of Change Across the Gulf: An Environmental Report on the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy gives a comprehensive look at the impacts and status of the coastline that stretches from Massachusetts to Nova Scotia.

Edited by Gerald Pesch, a research biologist for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Peter Wells, senior research scientist for Environment Canada, the 81-page report, published by the Gulf of Maine Council, includes research on the land uses, pollutants and fisheries that could endanger the Gulf of Maine and the Bay of Fundy. The report applauds a number of positive initiatives such as the growing network of monitoring programs and public education efforts, and the expansion of coastal protected areas.

In a recent interview, the Gulf of Maine Times spoke with the co-editors about the environmental realities facing the Gulf and its watershed. Here are some excerpts from that interview: |

Let’s start with the big question. How healthy is the Gulf of Maine?

P. Wells: The Gulf of Maine is presently quite healthy but there are vulnerabilities, and the quality, its long term health if you prefer, has declined. The current function of the system is not showing too many signs of deterioration. Contaminants are building up and some organisms are affected by chemicals or have reduced population numbers, but generally the system is still working. However, the quality of the system has degraded immensely in the last 400 years, from activities such as resource extraction, e.g., the fisheries, to dams and dyking and the coastal development of the 20th century. What we want to do is make certain the health stays high, and that the quality is returned to somewhere near the original. The Gulf will never return to a pristine state but we can reverse some of the indicators of the decline in the quality.

Of all the stressors to the Gulf system, land use seems all encompassing.

G. Pesch: The concern is that land use tends to be the source of the problems. We look at consequences in the water and they invariably source back to the land. Steady development and very clear patterns of sprawl are the prime sources of many problems. The good news is that it’s very early on. There’s an opportunity to manage land development with smart growth principles. So there are some simple things that local communities could adopt that could mitigate against the consequences of land use development.

The report spends a good deal of time on impervious surfaces as a major culprit of ecological degradation.

G. Pesch: Impervious or paved surfaces shed water very quickly so rain events tend to impact habitat. When there is an initial rush of water it erodes stream banks and delivers elevated temperatures. Increased temperatures reduces oxygen creating impacts on fish and marine habitats. As well, that rush of water tends to wash contaminants off the land surface, which is delivered with no mitigation into the water bodies. In some cases, mostly in the southern Gulf, communities have exceeded the 10 percent threshold level for impervious surfaces.

Why should someone living in a small town along the Bay of Fundy care about impervious surfaces in Newcastle, New Hampshire?

G. Pesch: Because the Gulf of Maine is a system. It is not composed of isolated pockets of water. Therefore impacts at any one point in the system can accumulate. As a semi-enclosed system it has a residence time of about a year. So materials coming off the land in New Hampshire can cycle around the Gulf. We’ve seen the impacts in larger systems that have not been good, like the Mediterranean and Baltic seas, which are also semi-enclosed. We want to avoid these problems by doing something now rather than reacting to a problem after it happens.

What’s the score card on contaminants?

P. Wells: The good news is that, in general, levels of toxic chemicals are low for the substances that we measure in our Gulfwatch program. The bad news is that the system is being exposed to a very wide range of metals and organic compounds, and other compounds that we are not currently monitoring such as flame retardant compounds, which are very ubiquitous in the system. There are many other compounds like that that we are not monitoring but should be. We need to expand our monitoring programs and we need to assess the impacts of combined exposures to these compounds. What we’re also still doing is looking at the effects of a single chemical on a single chemical basis, which is inappropriate. We have to start looking at the cumulative and combined effects on marine organisms of low level exposure to many chemicals.

And the fisheries?

G. Pesch: If you look at the fisheries historically, we’ve managed with our improved technologies to fish down most of the desirable stocks in the Gulf of Maine rather dramatically. We need to move to a higher level of stewardship so that we manage those stocks in some deliberate way rather than let the market drive the fishermen’s decisions. The evidence is overwhelming that that needs to be done. There are mechanisms in place that are beginning to do that. It’s not easily done when you’re trying to support a family. But for the long term sustainability, we need to become more deliberate about how we manage those stocks.

You indicate that environmental management of aquaculture has improved. Any other thoughts on how the industry can earn the trust of skeptics?

G. Pesch: There are some concerns around aquaculture that need to be actively dealt with and can’t be ignored. But in putting together the report we engaged the salmon growers communities very actively, sometimes in an agitated way. Nevertheless, that engagement with the industry is very healthy. With the aquaculture issue, it would be in the best interests of the industry to put in place some measures that could be presented for public scrutiny based on hard data and information. If that were done every two years you could gauge the progress in dealing with the environmental side of the operations.

So what are the next steps?

P. Wells: We need to institutionalize through the Gulf of Maine Council a process of periodically reporting on the environment so that we keep issues affecting the Gulf within the eyes of the public as well as politicians and managers. We should institutionalize a series of reports on the core issues that are promptly done and maybe every five years when we have enough of these done, we should attempt to integrate them, score the issues, and truly do a state of the environment report. This process should also involve a wide range of stakeholders, writers and reviewers, for the reports to be credible to the wider public.

G. Pesch: The challenge also is outreach and education. If there is a common understanding of what those issues are and what individual communities are contributing to those issues, then I think there would be greater motivation to come together with common strategies to deal with these situations.

© 2004 The Gulf of Maine Times |