Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

2004

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

Browse the archive |

|

|

|

|

Building a bridge, one phone call at a time

Art Longard Award winner Elsa Martz is one determined steward

By Andi Rierden, Editor

Elsa Martz at home in Harpswell, Maine Photo: Peter H. Taylor |

With encouragement from a local wharf builder who estimated that replacing the causeway with a wooden bridge would cost a mere $40,000, Martz stepped into full throttle and became an unflagging proponent of the Dingley Island tidal flow restoration project.

Over the next seven years, underscored by a series of high hopes, setbacks and successes, her campaign grew to involve dozens of individuals, local, state and federal agencies and private corporations. Though the initial estimate proved to be well below the mark, Martz and other restoration supporters kept chipping away. Last summer, a section of the barrier between the island and Harpswell was removed, one side at a time to keep the road open. Working with a private engineering firm, U.S. Navy Seabees then constructed a small, but wide-opened bridge, re-establishing water flow.

Skating to Sargasso

A freshwater biologist’s fascination with a sea skater

By Ethan Nedeau

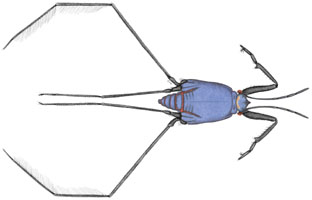

Illustration of Halobates © Ethan Nedeau |

I became a biologist because of my love for creatures—especially insects—living in freshwater streams, lakes and wetlands. Turn over some cobbles in a mountain stream in New Hampshire and you will find a rich diversity of larval insects.

‘Smoking gun’ images allow Massachusetts to flex its enforcement muscle

By Maureen Kelly

Private landowners who think

they can add a few more acres to their properties by filling in wetlands

should think twice. In an innovative new approach to resource management,

the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) is using

aerial surveillance and state-of-the-art technology to watch over the

state’s valuable wetlands, which play an important role in protecting

groundwater, buffering against floods and storms and providing wildlife

and fisheries habitat.

By comparing digital images of the land from the 1990s to those of today, DEP analysts are systematically mapping out and identifying areas where wetlands have changed over the years. The project is providing state regulators with new insight into what caused the loss of nearly 800 acres of wetlands in the eastern third of the state over the last decade.

At least 50 percent of the wetland losses are the result of illegal destruction, according to DEP Assistant Commissioner Cynthia Giles.

These findings prompted the state agency to shift priorities and develop a stronger presence in the field to enforce wetland protection laws and deter would-be violators, she said.