In hopes the dwarf wedgemussel survives

Presumed extirpated, surveyors have discovered new populations

By Ethan Nedeau

Printer Friendly Page

But more on that in a bit.

Not long ago, I drove north along the eastern flank of the Green Mountains before dawn, listening

to highway music and dreaming of discovery. Morning light filled the valley by five o'clock; from atop

a glacial escarpment my eyes followed a ribbon of mist hovering over the Connecticut River. I drove

into and out of river fog for a while as the highway descended into valleys and climbed mountains.

Then the highway took me away from the river for a jaunt through spruce-fir forests before finally

wending its way back to the river's silver maple floodplain in northern New Hampshire. The reflection

of the Dartmouth Range of the White Mountain National Forest was my last glimpse of the landscape for

a while. I donned SCUBA gear, descended ten feet below the surface, and worked slowly upriver in

search of the small and cryptic dwarf wedgemussel.

The dwarf wedgemussel (Alasmidonta

heterodon) is a freshwater bivalve that spends most of its life partially

buried in the bottom of rivers, with just the posterior end of the body

visible. Individuals are usually not more than 1.5 inches long and are

olive-brown or black. Dwarf wedgemussels could potentially live among

eight to nine larger and more common species in any single location throughout

their range, some of which outnumber them by more than 1,000 to 1 (such

as the eastern elliptio, Elliptio complanata). Because it is a

species of great conservation concern, surveys are routinely done to discover

new populations, monitor known populations and mitigate effects of projects

such as bridge and dam maintenance or bank stabilization. Such construction

and maintenance projects often cause mortality of mussels by dewatering

areas of the riverbed, changing physical habitat or by increasing sedimentation.

Finding dwarf wedgemussels requires a quirky mix of stamina, patience, devotion and masochism.

Searchers must look very carefully in the right place. The “right place” is an elusive concept that

has not yet been fully described; it is the Holy Grail for researchers who study the species. The

key seems to be stability, a somewhat murky concept that is difficult to measure and might have

different meanings in different rivers. Distinguishing areas that remain stable in extreme

conditions - such as droughts and floods - is critical to discovering mussels because they are

sedentary long-lived animals that are sensitive to environmental changes. It takes time to learn

to read a river and recognize telltale clues such as patterns of meanders, the slope of the land,

configurations of riffles and pools and ribbons of different substrates. For me, it's a feeling

more than a quantifiable set of variables.

Once you discover the right place, finding dwarf wedgemussels is mostly about pattern

recognition - training the eyes to discern between sticks, stones and other species of mussels

and learning to read a river on a small scale. It also requires enduring cold water, smothering

darkness, strong currents and creepy-crawly feelings of spending hours underwater. Even then,

you might spend hours or even days searching in vain before abandoning hope and concluding that

it simply does not, or has ceased to, inhabit a river. Patience and persistence sometimes yield

great rewards. An assistant and I once spent nearly 25 man-hours surveying a short distance upstream

of a dam and found only two dwarf wedgemussels - the first after 12 hours of effort.

Among the rivers where dwarf wedgemussels were presumed extirpated was New Brunswick's

Petitcodiac. Extensive surveys conducted in 1984, 1997 and 1998 could not find the species, and

the Canadian government formally declared that the species was extirpated from the Petitcodiac in

1999 after a 40-year absence, thereby also declaring it extinct nationally because the Petitcodiac

was the only Canadian watershed that supported the species. The declaration also meant that dwarf

wedgemussels were officially extirpated from the entire Gulf of Maine watershed because the species

only occurred in the Petitcodiac (except for a dubious historic record from the Merrimack River at

an unspecified location and date).

The dwarf wedgemussels of the Petitcodiac River represented a disjunct population - they were

separated from the species' core range to the west. Although dwarf wedgemussels were historically

documented in the Canoe and Agawam Rivers in southeastern Massachusetts and in the Merrimack River

near Andover, Massachusetts, the Petitcodiac harbored the only population farther to the east.

Watersheds in between - the Saco, Androscoggin, Kennebec, Saint George, Penobscot, Saint John and

countless smaller watersheds - which support some of the most viable populations of freshwater

mussels along the entire eastern seaboard, did not support dwarf wedgemussels. This assertion is

supported by many years of surveys in Maine, where surveyors (including me) have searched over 1,700

locations since the early 1990s. The Petitcodiac population was the zoogeographic puzzle piece that

had mystified researchers for decades. How did dwarf wedgemussels ever get that far east?

Dispersal is one of the more interesting traits of freshwater mussels. Though adults barely move

more than a few meters during their lives, the parasitic larvae (called glochidia) are released into

the water and attach to the fins or gills of a fish. Some species of mussels are very specific about

which fish their larvae will attach to, often using only a small fraction of the entire pool of fish

species in a waterbody. Dwarf wedgemussels are more specific than many species, and currently the

only species that are known hosts are the tessellated darter (Etheostoma olmstedi), Johnny darter

(Etheostoma nigrum), slimy sculpin (Cottus cognatus), mottled sculpin (Cottus bairdi) and juvenile

Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Tessellated darter is considered the primary host.

Freshwater mussels are only capable of long distance dispersal during the parasitic phase of

their lives, provided the fish are capable of, and actually swim, long distances. Of the dwarf

wedgemussel's known hosts, Atlantic salmon is the only species that can migrate long distances.

Though glochidia might remain on a fish for several weeks, they likely cannot survive in the ocean

(at least not long-distance transport), and there is no way that fish could have carried glochidia

from southern New England into eastern New Brunswick to begin a new population. So although dispersal

of mussels within a watershed is easily explained, dispersal into neighboring coastal watersheds is

not.

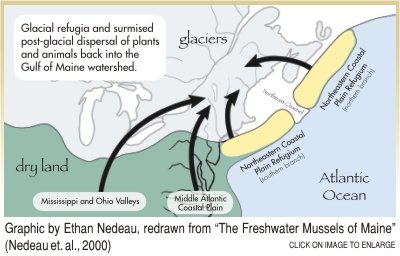

The Northeast Channel, a deep trench in between the Grand Bank and Georges Bank, divided the

glacial refuge that existed over the northeastern coastal plain into two pieces. Plants and animals

that had occurred throughout the Gulf of Maine watershed were separated for thousands of years until

the glaciers receded. As glaciers retreated, terrestrial and freshwater species dispersed back into

New England and eastern Canada along two routes - one across modern-day Nova Scotia into eastern New

Brunswick and eastern Maine, and the other into southern New England. Species with strong dispersal

abilities could have bridged the gap and filled Maine, whereas species with poor dispersal abilities

may have never bridged the gap. The disjunct population of dwarf wedgemussels in the Petitcodiac

might represent the only descendents of the populations that endured glaciation in the northern

piece of the northeastern coastal plain refuge. A few mussel species exhibit a similar range pattern

and strengthen this theory, including yellow lampmussels (Lampsilis cariosa), tidewater muckets

(Ligumia ochracea), brook floaters (Alasmidonta varicosa) and eastern lampmussels (Lampsilis radiata).

If the theories are true, the Petitcodiac population of dwarf wedgemussels had been genetically

isolated for more than 50,000 years, perhaps long enough for speciation to begin. Molecular and

genetic analysis might still reveal the degree of divergence from species in New England and the

mid-Atlantic states (because museum specimens are available). Ecological studies could have

revealed differences in life history traits and host fish. For one thing, tessellated darters

do not occur in New Brunswick or Maine. Of the dwarf wedgemussel's known hosts, only the Atlantic

salmon and slimy sculpin occur in eastern Maine and New Brunswick, and only Atlantic salmon are

known in the Petitcodiac. But other species could have also been hosts. These questions may never

be answered because the Canadian population is lost - they withstood the advance and retreat of

glaciers and persisted for millennia of environmental change, but vanished within decades of intense

human pressure.

Freshwater mussels are one of the most endangered groups of species on Earth. North America has

297 native species, and of those, 35 went extinct in the last century and nearly three-quarters are

considered imperiled throughout all or parts of their range. Seven of the 12 species in the Gulf of

Maine watershed are listed as endangered, threatened or species of special concern in at least one

state or province. The greatest threats are damming and channelization of rivers, sedimentation,

pollution (in countless forms from myriad sources) and introduced species. Even stressors that

have mild effects on their own could have synergistic effects with other stressors and greatly

exceed the tolerance of sensitive species. North America's rivers have been assaulted in countless

ways and its fauna - particularly fish and mussels - have suffered tremen-dously.

However, I am not going to drag you through a narrative of doom and gloom. In fact, I am an

optimist when it comes to freshwater mussels because I have a hard time believing in extinction.

I got goosebumps when I heard the story on National Public Radio about the ivory-billed woodpecker

and couldn't help but think about dwarf wedgemussels. Since the federal recovery plan for dwarf

wedgemussels was published in 1993, surveyors have found nearly 40 new populations in locations

where the species had been presumed extirpated or in rivers where the species had never been found.

The largest known population in the world exists in the upper Connecticut River in an area that

was denoted “historic, presumed extirpated” in 1993. This area hosts hundreds of thousands of animals.

While studying this population, an assistant and I found 1,441 dwarf wedgemussels in a 120 square

meter area - more animals than have been counted in all other locations combined in the last decade,

except perhaps the intensively studied population on the Neversink River in New York. Discoveries

or rediscoveries of dwarf wedge-mussels in the Connecticut River and many of its tributaries during

the last decade have given managers an entirely different view of the species, and this new

information is attributed to sampling effort. However, most surveys were designed to find the

species rather than provide rigorous population estimates and demographic analyses. We still do not

know population trends or how stable the species is throughout its range.

Scientists surmise that construction of a causeway between Moncton and Riverview in 1968 led to

the extinction of the Petitcodiac dwarf wedgemussel population. The causeway greatly reduced the

migration of anadromous fish such as American shad (Alosa sapidissima) and Atlantic salmon that

may have been important hosts. This cause-effect relationship has been shown in other rivers for

other species, such as the alewife floater that parasitizes alewife and shad. But in my long drives

to northern New Hampshire, passing by 10 dams before reaching the finest dwarf wedgemussel

population in the world, I can't help but wonder if blockage of anadromous fish passage really

doomed the dwarf wedgemussel population in the Petitcodiac. The population could have been

extirpated by other causes such as water quality issues, habitat degradation or a population

that was so small that recruitment failed and it dwindled to nothing.

In my quest to understand the dwarf wedgemussel and piece together patterns of zoogeography and

extirpation, the thing that torments me the most is the point at which we conclude that a species is

gone. Very few mussel surveys have ever thoroughly searched more than one percent of a river's

bottom. Sometimes it is easier to claim extirpation and write eloquently about causes than to submit

that surveys may have been ineffective at detecting a species with an extraordinarily low population

density and patchy distribution. Canadian researchers Andrea Locke, Mark Hanson and many others

have searched tirelessly for dwarf wedgemussels in the Petitcodiac, which might now be one of the

most intensively surveyed rivers in North America. Only with great reluctance and years of

waterlogged shoes did they conclude that the species was gone.

However, I am haunted by names of rivers where dwarf wedgemussels are presumed extirpated,

because I believe they could be in existence. In remote riffles, always around the next bend as

the sun sets or as the field season draws to a close, I imagine dwarf wedgemussels clustering

together to ride out the storm of change that we have created, waiting to flourish again once

our time has passed. I dream of finding these places in the Petitcodiac, Merrimack, Agawam,

Canoe, Quinnipiac, Schuylkill, Susquehanna and Potomac - as well as countless other rivers where

dwarf wedgemussels were never even discovered. These dreams of discovery fuel my long car rides

through the Connecticut River Valley, entertain me as I move slowly upriver in the muted underwater

world, and sadden me as I pack my SCUBA gear into the attic after a long field season.

© 2005 The Gulf of Maine Times

ALTHOUGH I have never set foot in its waters, the Petitcodiac River in New Brunswick is often on

my mind. A species has vanished from its waters, a missing piece of the puzzle that fuels my

enthusiasm for field biology. It may be the only freshwater mollusk to have been extirpated from

the Gulf of Maine watershed.

ALTHOUGH I have never set foot in its waters, the Petitcodiac River in New Brunswick is often on

my mind. A species has vanished from its waters, a missing piece of the puzzle that fuels my

enthusiasm for field biology. It may be the only freshwater mollusk to have been extirpated from

the Gulf of Maine watershed.

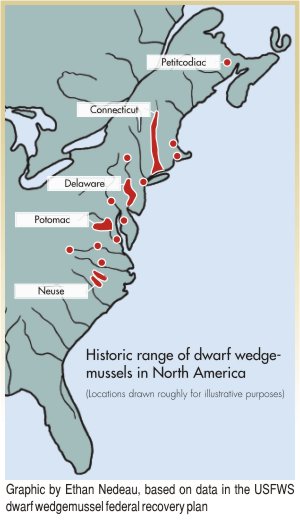

Historic and current range

The dwarf wedgemussel was first described in 1830 by Isaac Lea, who found them among specimens

collected in the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania (the species has not been seen in that river since

1919). Historically known from about 70 locations in 15 major drainages, the species appears to be

naturally uncommon in streams and rivers of Atlantic coastal drainages from North Carolina to New

Brunswick. It was listed as a federally endangered species in the United States in 1990. When the

federal recovery plan was published three years later, the dwarf wedgemussel was known to exist in

only 20 of 70 locations where it had originally been known to occur. Most of the populations were

thought to be small and declining. The federal recovery plan denoted all historic sites where animals

had not been recently collected as “historical occurrence, presumed extirpated.” The recovery plan

provided no rationale for the presumption that lack of recent records meant extirpation.

The dwarf wedgemussel was first described in 1830 by Isaac Lea, who found them among specimens

collected in the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania (the species has not been seen in that river since

1919). Historically known from about 70 locations in 15 major drainages, the species appears to be

naturally uncommon in streams and rivers of Atlantic coastal drainages from North Carolina to New

Brunswick. It was listed as a federally endangered species in the United States in 1990. When the

federal recovery plan was published three years later, the dwarf wedgemussel was known to exist in

only 20 of 70 locations where it had originally been known to occur. Most of the populations were

thought to be small and declining. The federal recovery plan denoted all historic sites where animals

had not been recently collected as “historical occurrence, presumed extirpated.” The recovery plan

provided no rationale for the presumption that lack of recent records meant extirpation.

Theories that focus on glacial history and post-glacial dispersal are promising. At the height

of the last glacial period (about 20,000 years ago), ice up to a mile thick covered the modern-day

Gulf of Maine watershed. Species found refuge either south of the glaciers or offshore on the

continental shelf (because the sea level was over 100 meters lower than it is now). Georges Bank

and Grand Bank were dry land, beyond the glacial maximum and were thought to have harbored many of

the species that subsequently recolonized the region as glaciers retreated. Pollen grains and

mastodon teeth have been found in marine sediment core samples taken at depths of 360 feet,

indicating a terrestrial realm 25,000 years ago. Perhaps additional cores would reveal dwarf

wedgemussels?

Theories that focus on glacial history and post-glacial dispersal are promising. At the height

of the last glacial period (about 20,000 years ago), ice up to a mile thick covered the modern-day

Gulf of Maine watershed. Species found refuge either south of the glaciers or offshore on the

continental shelf (because the sea level was over 100 meters lower than it is now). Georges Bank

and Grand Bank were dry land, beyond the glacial maximum and were thought to have harbored many of

the species that subsequently recolonized the region as glaciers retreated. Pollen grains and

mastodon teeth have been found in marine sediment core samples taken at depths of 360 feet,

indicating a terrestrial realm 25,000 years ago. Perhaps additional cores would reveal dwarf

wedgemussels?

Populations lost?

Ethan Nedeau is a science translator and illustrator for the Gulf of Maine Council. He can be reached

at ethannedeau@comcast.net.