Travelogue

Meeting whales on their terms in the Bay of Fundy

By Karen Finogle

The breaths come suddenly. Short bursts of moist air blown

urgently into the night sky. A mammalian geyser trades carbon

dioxide for oxygen before it slips beneath the surface. It’s

over in seconds. Perched on the edge of a cliff, at a campsite

50 feet (15 meters) above the ocean, I crane my head forward to

scan the murky darkness below. I wait…for a shimmering back

or barnacled head to break the surface. Nothing.

And then another blowhole sounds off. Twice this time. Another

follows minutes later. The whales surface in the shadows, avoiding

the single moonbeam that casts a carpet of light across the Bay

of Fundy. My chance to see these baleen feeders evaporates with

their invisible breaths.

Hearing them is its own magic. In a silence interrupted only

by the waves lapping against the rocks, these creatures surface

and exhale with voracity—as if they are on the verge of drowning.

In response, I quiet my own breathing and listen. My whole being

is tuned to their frequency, awaiting their missives.

My blubbery companions could be humpback or endangered North

Atlantic right whales, but they are likely finback or minke whales,

which are most often spotted from the shoreline. Members of all

four species spend the summer and fall months near Grand Manan,

a Canadian island in the Bay of Fundy that is 15 miles (24 kilometers)

long by almost seven miles (11 kilometers) wide.

Like much of the land that touches the Bay, Grand Manan has

some of the highest tides in the world, 27 to 30 feet high (8

to 9 meters), and they change every six hours. That’s the

secret behind what makes these waters such a four-star destination

for whales.

Approximately 100 billion tons of water is pushed in and out

of the Bay twice a day. This kinetic energy acts as a giant biological

mixer, churning up nutrients and bringing them to the surface

where phytoplankton—round, single-celled organisms that are

algae, bacteria or fungi—grow through photosynthesis. Phytoplankton

is the diet of zooplankton, tiny ocean animals that float at the

whim of ocean currents. And zooplankton is the food staple of

our baleen friends. Approximately 100 billion tons of water is pushed in and out

of the Bay twice a day. This kinetic energy acts as a giant biological

mixer, churning up nutrients and bringing them to the surface

where phytoplankton—round, single-celled organisms that are

algae, bacteria or fungi—grow through photosynthesis. Phytoplankton

is the diet of zooplankton, tiny ocean animals that float at the

whim of ocean currents. And zooplankton is the food staple of

our baleen friends.

I had begun my whale watch on the 90-minute ferry crossing

the Bay of Fundy from Blacks Harbour, New Brunswick, outside on

the deck until the stiff wind and pitch and roll of the ship sent

me inside to one of the vinyl, padded benches.

In the Bay, the endangered right whales, of which there are

only 300 to 350 left in the world, have the right of way. In 2003,

an international collaboration between shipping and oil companies,

scientists and the Canadian and U.S. governments led to the shifting

of shipping lanes four nautical miles east of established routes

in hopes of reducing collisions, which nearly always kill whales

if the vessel is large enough. Right whales, in particular, cannot

afford to lose even one animal if the species is to survive. The

shift diverts ships away from the primary feeding areas in the

Grand Manan Basin, an area of deep water between the island and

Nova Scotia, and has significantly reduced the number of whales

in direct exposure to vessels.

This year, that right-of-way will be extended, sort of. In

June, the Roseway Basin, an area 1,780 square nautical kilometers

southwest of Nova Scotia, will be designated as an area to be

avoided by container ships. Another example of international collaboration,

the new designation was adopted by the International Maritime

Organization last fall and will be in effect from June through

September each year. Unlike the Fundy regulation, this act is

voluntary, but shipping companies have historically been quick

to respond to such measures, and this particular act requires

only a minor route diversion.

The 50-degree Fahrenheit (10-degree Celsius) night air chills

me, and I must abandon my moonlit listening post on the northeastern

side of the island for the warmth of my sleeping bag. The tent

sits a mere 15 feet (4.5 meters) from the cliff edge, one of the

reasons I chose to come to the island and the Hole-in-the-Wall

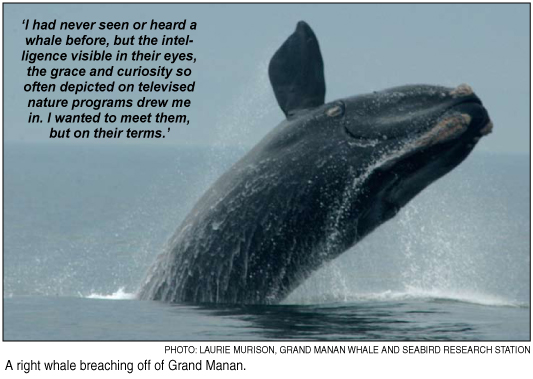

Campground. I had never seen or heard a whale before, but the

intelligence visible in their eyes, the grace and curiosity so

often depicted on televised nature programs drew me in. I wanted

to meet them, but on their terms.

With the advent of daylight, I am back scanning the ocean water,

waiting for the whales to move by, on their way to floating banquets

of zooplankton. Every wave that rises and breaks offshore tricks

me into looking closer, but Gray seals are my closest companions.

They are Neptune’s Labrador Retrievers, spinning and twirling

in the water, mimicking the joy their terrestrial cousins find

in rolling in the grass. They dive and surface in the fishing

weir that stands near the cliff walls–a primitive-looking,

kidney-shaped herring trap used by bands of Passamaquody and Mik’maq.

Seals seem adept at navigating the entrance to the stake and

twine net structures that stand like sentries around Grand Manan;

the tall, thin poles driven in the ocean floor jut out of the

water, visible even at high tide. I watch as a seal’s head

bobs on the outside of the net, ducks, and then resurfaces inside

only minutes later.

Once herring enters a weir, they follow the path of the netting,

the curved shape of which continuously directs the fish away from

the entrance. It can also confuse harbor porpoises, and even whales.

In one year, there were more than 300 porpoises caught in the

weirs around Grand Manan. Most years, about 15 to 30 get trapped.

Occasionally, minke whales, and sometimes humpback and right whales,

swim through the opening and then become confused; they have known

no such confinement in the ocean and cannot negotiate an exit.

Luckily, the Grand Manan Whale and Seabird Research Station, a

research organization established in 1981, has been working with

weir fishermen for several years to develop successful techniques

that free both porpoises and whales safely.

It’s a more difficult scenario in other parts of the ocean

where other types of fixed fishing gear provide invisible barriers.

Through photographic documentation, 75 percent of right whale

and humpback whale populations have scars from entanglements.

Some whales break free but carry fishing line wrapped around their

fins, tails or baleens. If tight enough, the lines can saw through

flesh and expose the whales to infection and possible death.

Entanglement and collision are the two biggest risks to right

whales currently, and the Grand Manan Whale and Seabird Research

Station, as well as several other organizations, is continuously

working to find new avenues of communication and collaboration

with government agencies and private industry to identify ways

to reduce these threats.

My last night on Grand Manan, I again scramble to the cliff

as the moon begins to rise on the eastern edge of the Bay of Fundy.

It is quiet except for the white noise of water against rock and

the occasional laughter from nearby campers. I wait for the whales

to return, for the final breaths or calls that will include me

in their community, if only for a moment. I sit patiently as my

muscles grow stiff. Nothing but the sound of surf reaches my ears.

Underwater, somewhere else, they are probably calling to each

other. They are social creatures that rely heavily upon communication,

and hearing is perhaps their most important sense. The Bay, the

entire ocean really, has been getting louder. Increased shipping

traffic, blasting, harbor dredging, fishing, and even whale watch

tours all add noise to the ocean. And the Bay of Fundy is already

a naturally noisy area, where the tides alone can cause a whale

to raise its voice.

If only I could shout down to them, my voice penetrating the

water and riding the currents until it reached their ears. What

would I say? Would I apologize for all the other noise, for the

clutter we’ve added to their saltwater home? Would I stutter

and stumble, the awkward visitor at a family gathering?

I think I would simply start with a “hello” and listen

to what they had to say; the sound of their breathing has already

taught me so much.

Karen Finogle, a free-lance writer and senior editor at

AMC Outdoors, lives in Durham, New Hampshire.

|