|

Visionaries: Protecting the future of

the Gulf of Maine

Making a difference

By Susan Llewelyn Leach

[printer friendly page]

Each year, the Gulf of Maine

Council gives out Visionary and Longard Awards recognizing innovation,

creativity and commitment to protecting the marine environment

of the Gulf of Maine. The Visionary Awards are presented to two

individuals, businesses or organizations within each state and

province bordering the Gulf of Maine.

One Longard Award is presented

to an unpaid individual from one of the five states and provinces

who is dedicated to environmental protection and sustainability

of natural resources within the marine, near shore and watershed

environments of the Gulf of Maine (see story on Roger Berle,

Pages 1,8). The award is named in memory of Art Longard, a founding

member of the Gulf of Maine Council.

Massachusetts

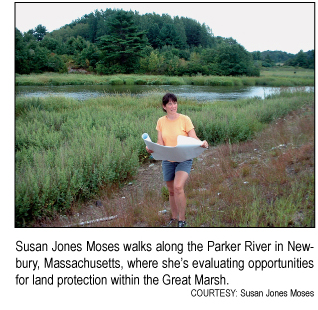

Susan Jones Moses

Growing up in the shadow of the

six-million-acre (2.4-million-hectare) Adirondack Park in New

York State, Susan Jones Moses was never far from open spaces

and natural water — the type of environment she now works

so hard to protect in Essex County. Growing up in the shadow of the

six-million-acre (2.4-million-hectare) Adirondack Park in New

York State, Susan Jones Moses was never far from open spaces

and natural water — the type of environment she now works

so hard to protect in Essex County.

When she first moved to the North

Shore of Massachusetts in 1992, she said she was struck by the

pace of development. In her own town of Rowley, which sits on

the edge of Great Marsh, agricultural land was rapidly disappearing

to new housing. Jones Moses went to work. Combining her expertise

as a planning consultant with her flair for distilling complex

issues into terms people could understand, she built local support

for town overrides and laws that now protect more than 400 acres

(162 hectares) of the marsh’s watershed.

Her successes in Rowley as a

volunteer crisscrossed with her planning career and led to a

contract with the Essex County Forum. The county’s 34 communities

now look to her for zoning and land protection advice. While

she sees her job as part education, part technical assistance,

often the biggest challenge is getting property owners to recognize

the connection between the land and marine environment, she said.

“Whatever people do on their land doesn’t just stay

on their land,” she explained. “Their actions affect

the sea a mile (1.6 kilometers) away.”

Her educational push also comes

in the form of workshops on smart growth issues for local planning

and zoning boards. She argues for open space protection to be

an integral part of affordable-housing design. At the most fundamental

level, she challenges people to think outside their own interests.

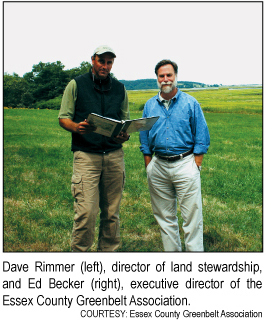

Essex

County Greenbelt Association Essex

County Greenbelt Association

Ed Becker reckons there are two decades left to make a difference.

The executive director of the Essex County Greenbelt Association

is referring to the nonprofit’s conservation efforts. Over

the years the land trust, based on the North Shore of Massachusetts,

has steadily acquired parcels of land that have ecological, scenic

or agricultural value. But as prices soar and development encroaches,

the opportunity to protect is diminishing.

“We know that 25 percent

of the land base left is available for development,” Becker

said. But not all of that is worth conserving. As the window

closes, Greenbelt is becoming more strategic and proactive in

reaching out to landowners,Becker said.

In 46 years, the association

has protected more than 12,000 acres (4,856 hectares) of land

and transformed 4,500 acres (1,821 hectares) of that into a reservation

system open to the public. Some of those parcels skirt Great

Marsh and offer unique opportunities to bird watch, hike and

canoe. Walks, talks and a guidebook are all part of the organization’s

educational output along with information on the natural history

of all the reservations.

As its name suggests, Greenbelt

is keen to create natural corridors along rivers, streams and

coastlines both for the view and the environmental benefit. Past

successes and a reputation for getting things done have aided

that quest, Becker said. The organization is often approached

by owners wishing to gift their property or create a conservation

easement.

Increasingly, he said, Greenbelt

is using that real estate experience to assist cities and towns

in Essex County to protect more open space and compound the conservation

effort.

New

Hampshire New

Hampshire

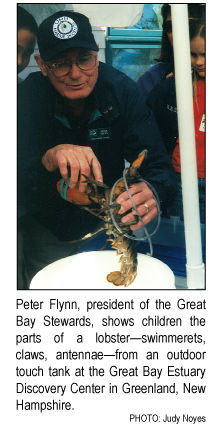

Great Bay Stewards

Each day salt water comes rushing up the Piscataqua River in

a 10-mile (16-kilometer) race to meet fresh water in New Hampshire’s

Great Bay. That mingling of sea and river in the country’s

most recessed estuary has created a unique ecosystem, one that

the Great Bay Stewards are working to protect.

The Great Bay National Estuarine

Research Reserve was established in 1989, and five years later

a Discovery Center was built at Sandy Point on the bay. The Stewards

came along in 1995 to support the reserve and the center, monitor

the watershed and organize fund-raising and educational events

for children and adults.

Each year, the Stewards offer

two University of New Hampshire students $1,000 each to do a

research project on the bay. One project last year measured the

nitrogen levels around the bay and thus the pollution, said Peter

Flynn, the president of the Stewards.

As their name suggests, the Stewards

regularly check that no building or dumping is going on in lands

with conservation easements along the bay’s shores. But

the biggest challenge, Flynn confided, is providing funds and

assistance to volunteer efforts. With the help of its 200 members,

the nonprofit organizes many fund-raising events, such as 5K

races and art shows. And although each event doesn’t bring

in large sums, he said, the public learns of the conservation

efforts for the bay. And that educational outreach is just as

critical. “It’s amazing to me how many people who have

lived here for years don’t know what the Great Bay estuary

is all about,” Flynn said. “Many still think it’s

a lake.”

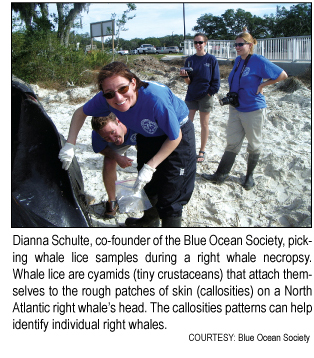

Jen

Kennedy and Dianna Schulte Jen

Kennedy and Dianna Schulte

If you want to capture children’s attention, introduce them

to a 60-foot (18-meter) inflatable fin whale. That’s the

approach of Jen Kennedy and Dianna Schulte, who use the home-made

mammal in school presentations on the marine environment.

The two whale-watch naturalists

and cofounders of The Blue Ocean Society for Marine Conservation

work hard to engage children and the public. To that end, the

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, nonprofit coordinates with four local

whale watch companies and offers presentations to waiting passengers.

Since people learn in different

ways, Kennedy said, the naturalists try to address all the senses

— through whale sounds, reading materials, touch tanks and

talks. The touch tanks, an idea Kennedy developed with the help

of interns, sits dockside full of small sea creatures people

can meet up close. But perhaps not too close since they include

crabs, sea urchins and sea stars.

Education is only half the story.

Blue Ocean collects data on marine life from the whale boats

and tracks floating debris. Whale fins are photographed and a

detailed record of each mammal’s behavior noted and catalogued.

All this data is then shared with other whale research organizations

in Maine and Massachusetts and made available to the public.

It even becomes the basis for science projects in schools.

Blue

Ocean’s research on endangered species also helps conservation

efforts and is used to identify areas that need protection. Regular

beach cleanups and an Adopt-a-Beach program begun in 2004 have

become successes, with 25 “adoptions” so far. Blue

Ocean’s research on endangered species also helps conservation

efforts and is used to identify areas that need protection. Regular

beach cleanups and an Adopt-a-Beach program begun in 2004 have

become successes, with 25 “adoptions” so far.

Maine

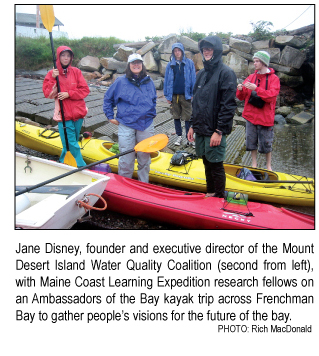

Jane Disney

Jane Disney claims no credit. She said her students took her

places she didn’t have the courage to go. The Mount Desert

Island Water Quality Coalition (MDIWQC) grew out of their initiative,

the former biology teacher said. And in the space of a few years,

since its inception in 2000, the coalition has lived up to its

name. By drawing together children, college students, island

residents, businesses and fishermen into its projects, it has

built community awareness of the local watershed and fundamentally

changed people’s behavior.

It all started at Seal Harbor Beach. There, the

students monitored water quality to identify pollution issues

that threatened public health. From that the coalition gathered

momentum and now includes regular surveys of clam flats and the

shoreline; plankton and beach monitoring; research and education

at its bio lab and the Community Environmental Health Laboratory,

which runs in partnership with the MDI Biological Laboratory

in Salisbury Cove (Bar Harbor); and student internships and community

outreach programs. It all started at Seal Harbor Beach. There, the

students monitored water quality to identify pollution issues

that threatened public health. From that the coalition gathered

momentum and now includes regular surveys of clam flats and the

shoreline; plankton and beach monitoring; research and education

at its bio lab and the Community Environmental Health Laboratory,

which runs in partnership with the MDI Biological Laboratory

in Salisbury Cove (Bar Harbor); and student internships and community

outreach programs.

Many projects have become an

integral part of the region’s school science curriculum.

For third graders, that means trooping out to storm drains, collecting

data about the trash around them and stenciling a large stylized

fish and warning sign. This alerts the public that the drains

dump directly into the bay.

The children get “pretty

worked up about runoff,” said Disney, now executive director

of MDIWQC. It’s an example of how youthful energy can galvanize

town council members into acting on their responsibility to the

next generation, she said. “Kids here are leading the call

to action.”

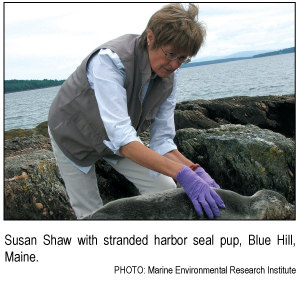

Susan Shaw

The issue seems surprisingly simple. People understand when humans

are at risk from toxic chemicals, but they don’t recognize

when marine mammals are, said Susan Shaw. And nor do they see

the significance of the link between the two. Her institute’s

groundbreaking research into harbor seals is exposing that connection

and changing public policy along the way.

For

several years, the Seals as Sentinels project, run out of the

Marine Environmental Research Institute Shaw founded in Blue

Hill, Maine, has been identifying alarming levels of pollutants

in the Gulf of Maine’s harbor seal populations. Along with

PCBs, Shaw discovered rising concentrations of flame retardants

in the seals. That was a first. Not only did the flame retardant

data attract international attention, it influenced the state’s

decision to ban the most widely used commercial form, DecaBDE.

For this work, the state of Maine honored her with a special

Citation of Recognition. For

several years, the Seals as Sentinels project, run out of the

Marine Environmental Research Institute Shaw founded in Blue

Hill, Maine, has been identifying alarming levels of pollutants

in the Gulf of Maine’s harbor seal populations. Along with

PCBs, Shaw discovered rising concentrations of flame retardants

in the seals. That was a first. Not only did the flame retardant

data attract international attention, it influenced the state’s

decision to ban the most widely used commercial form, DecaBDE.

For this work, the state of Maine honored her with a special

Citation of Recognition.

From small beginnings 17 years

ago, Shaw’s research institute — with marine labs,

a field station and an aquarium that mimics the Gulf of Maine’s

ecosystem — has been gaining international recognition for

its scientific leadership. And Shaw is the gently-spoken force

behind those breakthroughs.

Her path to this point has been

marked by a desire to understand the world, she said, to find

new ways of seeing, whether through photography, public health

or marine research. She shares that understanding liberally.

In the international arena, she gives papers at conferences,

this year in Tokyo and Cape Town. Locally, her institute offers

water quality monitoring, educational programs and an environmental

lecture series.

Shaw said she feels some urgency.

The United States was late to the table in recognizing the ocean

crisis, she said. “I hope it’s not too late.”

New Brunswick

Greg Thompson Greg Thompson

Fishermen are an independent lot. And they pride themselves on

it, said Greg Thompson, a lifelong fisherman of New Brunswick’s

waters. But over recent years aquaculture, liquefied natural

gas terminal tugboats and other claims to the open ocean have

encroached on that celebrated independence. The shift has not

been easy.

As a founding member of the Fundy

North Fishermen’s Association in the late 1970s, Thompson

has had fishermen’s interests in his sights for years. Of

the 150 or so fishermen in Fundy North almost half are members

of the voluntary organization — an achievement in itself.

But what particularly encourages him is their growing awareness.

“Our fishermen are a little more open to looking at the

good of the fishery as a whole — open to the concept that

it is a common property or resource,” he said. “It’s

a form of maturity.”

That accomplishment didn’t

come without decades of effort and initiative. Years ago, when

the government imposed quotas to halt declining ground fish stocks,

battles ensued. Each fisherman wanted at least what he or she

had before, Thompson said, if not more. “We fought each

other over each fish.” Out of that head-to-head grew community-based

fisheries management, a system Thompson helped develop. It allocates

quotas to fishing communities rather than individual fishermen.

The main benefit: Communities manage to keep their small fishing

enterprises. That’s key, he said, because when a community

loses its fishery, it’s like losing a school or a church

— a valuable dimension disappears.

Building consensus is a theme

for Thompson. It’s the only way ahead, as he sees it. So

as the demands on the Bay of Fundy grow — from fisheries

and aquaculture to tourism and industry — he’s working

hard alongside others to integrate them in a marine planning

process for southern New Brunswick.

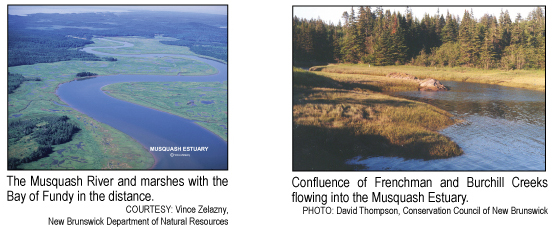

Friends of Musquash

Estuaries offer a rare meeting of salt water and fresh. In that

tidal mix, they support a wide range of wildlife and marine species.

Musquash Estuary on the Bay of Fundy is a rarer spot still —

an estuary whose ecology and salt marshes have remained largely

intact over the decades. A 1990 study identified it as the only

estuary in the region not subject to major development: no seaport,

aquaculture, industry, dredging or residential buildup.

That

confluence of conditions led the Conservation Council of New

Brunswick and the Fundy North Fishermen’s Association to

propose making the estuary a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in 1998.

In March 2007 it became an official MPA. That

confluence of conditions led the Conservation Council of New

Brunswick and the Fundy North Fishermen’s Association to

propose making the estuary a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in 1998.

In March 2007 it became an official MPA.

One of the biggest players in

nudging the project forward during those years was the Friends

of Musquash, a group of local residents, stakeholders and interest

groups. Formed in the late 1990s, the Friends facilitated forums

and coordinated with government officials over future management

of the MPA.

David Thompson, the president

of Friends, attributed much of the ultimate success of the venture

to the perseverance of local residents, people who have lived

on the edges of the estuary for generations and wholeheartedly

supported the proposal.

Now that the MPA is in place,

the Friends will become “the eyes and ears surrounding the

estuary,” Thompson said. Members will do field work the

government is too understaffed to carry out and offer on-the-ground

guidance and advice to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, which oversees

the eight-mile (13-kilometer) estuary.

Nova Scotia

Clifford Drysdale

Turtles are known to be slow. But in southwest Nova Scotia, the

Blanding’s variety is also a distance walker. That was one

finding of the Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute (MTRI) project

to advance habitat connectivity for species at risk.

The

Blanding’s turtle recovery team researchers worked in cooperation

with staff, trustees and representatives from various levels

of government. The results influenced a local logging company

to set aside a patch of land to accommodate the turtles’

wanderings and protect nesting sites. The

Blanding’s turtle recovery team researchers worked in cooperation

with staff, trustees and representatives from various levels

of government. The results influenced a local logging company

to set aside a patch of land to accommodate the turtles’

wanderings and protect nesting sites.

It’s one small example of

MTRI’s collaborative approach to research, said Clifford

Drysdale, the institute’s chairman and chief executive officer.

Forestry is the primary industry in the region, yet there’s

an open cooperation between landowners, scientists and loggers.

That weaving of different interests

is part of MTRI’s role, which Drysdale described as a combination

of catalyst and partner. Established in 2004 by a group of scientists

with the support of industry, educators and local residents,

the institute has quickly become a hub of new research, data

exchange and education programs, all in the service of promoting

sustainable use of resources and biodiversity conservation.

With 30 years’ experience

as an ecosystem science manager at Kejimkujik National Park and

National Historic Site in Nova Scotia, Drysdale, now retired

from Parks Canada, is in his element. Still, the public’s

interest and enthusiasm for the institute’s volunteering

and monitoring programs have been especially encouraging. It

seems to have caught the imagination of the local people, he

said modestly. Children meet and talk to the scientists as part

of school programs. And research is openly shared with the public

as a way to promote conservation.

Coastal Communities Network

The heart of the Coastal Communities Network, said Executive

Director Ishbel Munro, is its ability to provide a meeting ground

for a broad range of voices and views. Fishermen rub shoulders

with church people, First Nation members share ideas with Acadians,

and environmentalists chat with youth groups.

It’s

a network with a big goal: to sustain the social and economic

well-being of the small communities that skirt the province’s

coast and dot its rural inland. It’s

a network with a big goal: to sustain the social and economic

well-being of the small communities that skirt the province’s

coast and dot its rural inland.

It all started with the cod crisis.

In the early 1990s, the ground fishing industry collapsed and

with it much of the economic fiber of the region. Munro worked

on a committee that organized a series of seminars to discuss

the crisis, drawing together all threads of the community. These

were people who had rarely stood in the same room, let alone

discussed fisheries. It was time to set differences aside, Munro

said. It became the unofficial beginning of the Coastal Communities

Network (CCN).

From there, CCN has grown into

an information clearinghouse and generator of creative solutions

for local communities. It holds rural policy forums and workshops,

and gathers research that communities can draw upon to address

their own needs. It also publishes a magazine and maintains a

resource-rich Web site. In isolated communities particularly,

Munro said, the monthly meetings can be a lifeline and offer

much-needed moral support.

One of CCN’s biggest successes

has been its work on wharfs. “They’re how [you] get

to work if you’re a fishing person,” she said, describing

them as the linchpin of coastal communities. With 255 wharves

in Nova Scotia, the maintenance bill has been overwhelming. CCN

jumped in and helped secure federal funding. Then the network

did what it excels at: it held workshops to educate people about

the role wharves play in the economy and community.

Susan Llewelyn Leach is a

free-lance writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

|

![]()