Book Reviews

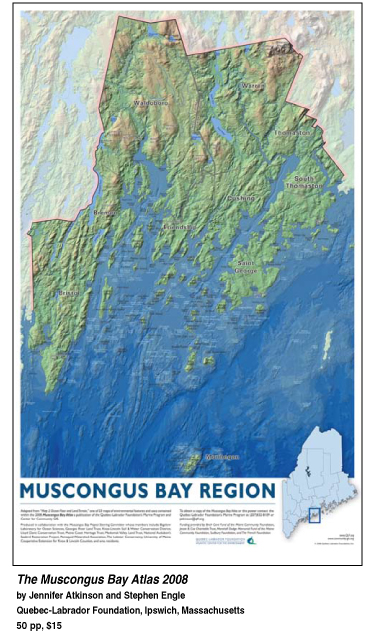

The Muscongus Bay Atlas 2008 The Muscongus Bay Atlas 2008

Reviewed by Nancy Griffin

A new publication that maps the coastal marine areas of Muscongus Bay offers specific information about this one bay area, but also offers a framework for people in other estuaries, communities and organizations to do the same.

The introduction states, “The Atlas is for anyone who has an interest in learning more about Muscongus Bay. It is also for people who like maps.”

The Muscongus Bay Atlas 2008 was produced by the Quebec-Labrador Foundation/Atlantic Center for the Environment in Ipswich, Massachusetts, which has a Marine Program based in Waldoboro, Maine, directed by Jennifer Atkinson.

A quote from the introduction to the Atlas explains why the project was conceived: “Although located at the midpoint of Maine’s long coastline, Muscongus Bay is not all that well known to many in New England... often overshadowed by... Penobscot Bay to the east and the... Damariscotta River Estuary to the west. Those who live here (close to 23,000 year round), however, are passionate about its beauty, its ‘out of the way’ location, and its traditional, rural character.”

Atkinson and Stephen T. Engle, GIS director for QLF, produced the Muscongus Bay Atlas 2008, but the acknowledgments include a long list of fishermen, environmentalists, scientists, municipalities, academic and historical groups.

The Atlas is “an experiment. In all our searches, we found nothing like it,” Atkinson said. “While a lot of GIS data changes, it’s the digital library that underlies the Atlas that is the true power behind it. We can update that much more frequently than the published maps.” Two other marine regions have already inquired about producing similar resources.

Set up as one page of data describing the map that appears opposite it, the Atlas covers commercial fisheries, with special maps for the lobster fishery, geology, the ocean floor and land terrain, kayaking areas, watersheds, sea level rise predictions, sailing areas, soils, population and housing growth, working waterfronts and more.

“This collection of maps gets us... into new possibilities for using maps and digital data in local decision-making,” wrote Atkinson in the Atlas. “It is a launching point from which we can begin to visualize and discuss our common issues and resources.”

The huge file is available in several formats -- to view or download online in its entirety, in sections or just images. Print copies cost $15 in bookstores, plus $5 S&H ordered by mail.

Besides QLF, the Atlas was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Birch Cove Fund of the Maine Community Foundation, Davis Conservation Foundation, Jessie B. Cox Charitable Trust, Knox County Fund of the Maine Community Foundation, Maine State Planning Office, Marshall Dodge Memorial Fund of the Maine Community Foundation, The French Foundation and University of Maine Cooperative Extension for Knox & Lincoln Counties.

[ back to top ]

Sharing the Ocean: Stories of Science, Politics, and Ownership from Sharing the Ocean: Stories of Science, Politics, and Ownership from

America’s Oldest Industry

Reviewed by Lee Bumsted

While it may seem paradoxical to assert that commercial fishermen are some of the best people to manage and protect the New England inshore fishery, that is precisely what Michael Crocker does in Sharing the Ocean: Stories of Science, Politics, and Ownership from America’s Oldest Industry.

He makes a persuasive case that inshore fishermen, with their detailed knowledge of local ecosystems and a desire to conserve the resource they harvest, should have a greater role in determining fishing regulations.

Various management plans to stem the decline of the New England groundfish population have been tried over the past 30 years. Crocker summarizes these regulations and chronicles some of the missteps taken by well-intentioned federal regulators and environmentalists.

He describes how quotas on the amount of fish taken and days-at-sea limits have disproportionately hurt fishermen working on smaller vessels with limited ranges. These fishermen often hail from rural coastal ports, so their loss of income or livelihood radiates out to their communities as well.

Crocker worked as the communications director for the Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance (NAMA) from 2001 to 2006, and he devotes a chapter of this book to the work of NAMA and an extensive survey it conducted. The nonprofit organization promotes community-based management of the fishery in which fishermen join scientists, environmentalists, and policy makers in collaborating on regulations.

NAMA’s Fleet Visioning Project looked for common threads in the replies to a survey distributed to New England groundfish permit holders, researchers, marine business people and managers. Respondents were asked their vision of the future of the groundfish fleet, why it is important to them, and how they could help. Survey results were shared at regional workshops, sent to participants and fishery managers, and published online at www.namanet.org.

The final segment of Sharing the Ocean makes compelling reading, and is the section most accessible to general readers. It consists of 31 short narratives gathered from the Fleet Visioning Project. In their own words, stakeholders tell why they want to help the local fishery succeed. Their stories are paired with full-page color portraits by Rebecca Hale, a studio photographer for National Geographic.

Howdy Houghton from Bar Harbor, Maine is one of the many fishermen profiled. He said: “....we need to consider just how dependent our communities are on fisheries as a food source and take care of the fish. We must use wise local stewardship to maintain healthy local seafood ecosystems for future generations, and for cultural, economic, and local seafood security.”

Jennifer Brewer, a geographer in New Harbor, Maine, offered this observation: “If we lose our fishing industry, or allow it to consolidate unduly, we lose a big chunk of our soul -- as individuals, communities, states, and society at large.”

These narratives and portraits bring alive the values of those involved in the inshore fishery. They also support Crocker’s thesis that local commercial fishermen have much to contribute to solving the fishery management dilemma.

"An Enormous, Immensely Complicated Intervention": Groundfish, the New England Fishery Management Council, and the World Fisheries Crisis "An Enormous, Immensely Complicated Intervention": Groundfish, the New England Fishery Management Council, and the World Fisheries Crisis

Reviewed by Nancy Griffin

Fisheries management is a contentious and precarious field, fraught with the perils of economic disaster for fishing families and communities, the possibility of stock depletion despite best efforts, and frustration for managers when plans fail.

Since its inception in 1977, members of the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC) have witnessed or experienced all these things. Moreover, they have been blamed for causing most of the region's fisheries problems.

The authors have written this book to set the record straight. They are expert witnesses, since marine biologist Spencer Apollonio of Boothbay Harbor, Maine, spent more than 20 years in fisheries management and science. He served as executive director of the council for its first two years and as a member for eight more, and served more than 10 years as Maine's Commissioner of Marine Resources.

Jacob J. Dykstra of Wakefield, Rhode Island, spent six decades in the fishery as a fisherman, founder of a fishermen's co-op, member of the U.S. delegation to Law of the Sea Conferences for the United Nations, and active participant in the effort to place a 200-mile exclusive fishing zone around the U.S. He also served on the council for seven years, and as chairman for one.

Starting with the introduction, the authors take off the gloves to criticize the analyses of New England's fisheries crisis by other experts, deeming them to be of "varying validity" but say none "identify fundamental causes of and offer credible arguments for failure."

The title of this work, which first traces the history and problems of New England's fisheries management policies for the council's first 10 years, is taken from Margaret Dewar's 1983 book "Industry in Trouble." The entire sentence from her book reads: "Planning for the use of the fisheries constituted an enormous, immensely complicated intervention in the structure of an industry, in the level and distribution of income in the industry, and in the nature of communities dependent on the industry."

When created, regional councils around the country were charged with creating plans to manage commercial species at a time when no one had any experience creating such plans.

Industry participants were elated at first about the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MFCMA), the regional council system and the exclusive 200-mile limit that would protect U.S. fisheries from the huge, efficient foreign fleets. These fleets had been depleting the resource for several years, steaming regularly to Georges Bank, the Gulf of Maine, the Nantucket Shoals as well as other nearshore fishing grounds off Canada.

New England fishermen believed that with their smaller, less efficient vessels and more stringent conservation measures such as larger net mesh sizes to allow escapement of juvenile fish, they could surely never do the harm the foreign vessels did.

The first NEFMC management plan in 1977 covered three groundfish species: haddock, cod and yellowtail flounder, calling for a total allowable catch and a shutdown of the fishery once the quota was reached.

Elation soon died when the quotas were caught early and managers were faced with closing down the fishery. At the end of Chapter 2, Encountering Reality — the Cod Crisis of 1977, Apollonio and Dykstra write:

"Within four months of the implementation of the plan that was to last for the full year, and less than six months into its first year, the council was faced with a major crisis, the likely disruption of the multi-million dollar fishery."

The history proceeds from there, through more plans, more crises, more attempts to rebuild the stocks -- with some success, but at great cost to fishermen. Most recently, the fishing limits for New England groundfish harvesters were reduced to 20 days, when in the days before trip limits, crews averaged more than 220 days of fishing annually.

While explaining and justifying some of the council's methods, Dykstra and Apollonio do not try to shift the blame to another entity, but point out that in their opinion the system of management now in place is seriously flawed and has been from the start.

New England's council in particular, has been singled out by critics around the country as a failure of management. The authors quote writers who say NEFMC was controlled by members of the industry and their vested interests. Critics said the Council was "a classic case of the fox guarding the henhouse" or that fishermen "dominated" the council's actions.

The authors point out that with the diverse ports, gear types, vessel sizes and wildly different targeted fishing species, any fewer than the six industry representatives -- from fishermen to processors to dealers -- out of 17 council members would have been under-representing the industry.

The process now is driven by law suits, management plans increase in complexity with every incarnation, each re-authorization of MFCMA sees a large number of proposed amendments to management plans "suggesting that there is continuing hope that a revision or change in the law here or there will somehow improve the situation." The authors think not. They believe the system is flawed beyond tinkering and needs a fresh start.

"We can document enough examples of tactics that did not work to suggest the necessity to question traditional assumptions underlying fishery management," state the authors in Chapter 3, The Objectives of the Book. Here they list the three fundamental changes they suggest and that the rest of the book will document by detailing the history and quoting the literature written about NEFMC and the fisheries crisis.

The three changes they recommend are: 1) benign and selective fishing technologies; 2) truly effective methods for control of fishing effort, or more properly, of fishing mortality; and, 3) understanding of the structure and functions of fisheries ecosystems.

They also place the New England situation squarely in the context of fisheries worldwide. Despite a completely different management system, Canada's cod stocks also plummeted. Europe and other parts of the world with their different management regimes have faced and are still experiencing fisheries crises.

Readers interested in fisheries, especially in New England's fisheries, will get all the detail they ever wanted about the management process, the historical data and salient bits from much of the literature written after the fact of the 200-mile limit and about the current management system.

Acknowledging that the context of fisheries is economic, the authors also explain their interest in the "hierarchy" of fishing, stating: "Economics constrains the fishing industry, which constrains the natural community that constrains individual species. Both economics and the fish community must be equally incorporated in this proposal... not attempt to directly manipulate the stock size of any single species... it is more effective to preserve the context in which individual species may vary within natural limits set by the constraints of the context.

"Our model therefore, proposes to monitor the collective rate of investment in the fisheries -- all of the fisheries of the region -- and the rate of biomass removals from the fish community of the region. It is rates that are of primary interest, not absolute numbers." (Authors' italics)

The authors also provide a long list of reference works, a thorough index, a list of acknowledgments, a glossary and a page of abbreviations and initials of industry terms and agencies.

[ back to top ]

|