![]()

Volume 6, No. 1

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

||||||||||

|

Regular columns |

|

Archives |

|

About |

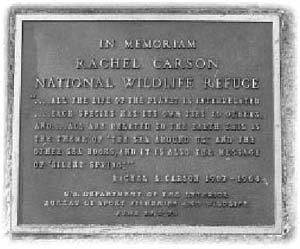

Forty years on, Carson's legacy continues

By the time Rachel Carson built her summer cottage in Maine, she had become an internationally known author and biologist. The book most responsible for her celebrity, The Sea Around Us, published in 1951, moved quickly to the best-seller lists where it remained for 86 weeks, 39 of them in first place. It won the John Burroughs Medal and then the National Book Award. Within a year, the book sold 200,000 hard copies. Carson first saw and became enchanted with the mysteries of the oceans while studying at the Marine Biological Laboratories in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Later, as an aquatic biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service she wrote four widely distributed pamphlets describing over 70 fish and shellfish.

From the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge

Courtesy of Ward Feurt, USFWS

The Sea Around Us allowed Carson to retire from USFWS to

write full-time. With proceeds from the book, she bought property on

Southport Island near the mouth of Maine's Sheepscot River. There Carson

weaved many of her investigations of tide pools and woods surrounding her

home into her later sea books. She spent 12 summers in Southport from 1951

to 1963, and eventually enlarged her small cottage to accommodate her

mother, niece Majorie and grandnephew Roger.

All of Carson's sea books praise the living ocean as an intricate and

interconnected natural system. In each she describes in a precise, literary

style the relationship between the largest cycles of nature and the

processes within living cells. In The Sea Around Us she uses the example of

the convoluta, a small worm that lives in sandy beaches and is host to a

green algae inside its body. Each time the tide recedes, the worm emerges

from the sand so its algal cells can carry on photosynthesis; when the tide

returns, the worm sinks back into the sand to avoid being washed out to sea.

Placed in an aquarium with no tides, the convoluta continues to rise to the

sun twice a day.

In The Edge of the Sea Carson continued to stress the ecology of the sea and its link to all other life forms. "To understand the life of the shore," she wrote in her preface, "it is not enough to say, 'This is a murex' or 'That is an angel wing.' True understanding demands intuitive comprehension of the whole life of the creature that once inhabited this empty shell: how it survived amid surf and storms, what were its enemies, how it found and reproduced its kind, what were its relations to the particular sea world in which it lived."

Carson's essay, "An Island to Remember," about the history of Indiantown Island, Maine is considered by some to be her best nature writing. "When I look at the island I think of her," says Dawn Kidd, the executive director of the Boothbay Region Land Trust and the person largely responsible for creating the Rachel Carson Coastal Greenway. Dedicated in 1996, the protected areas run from Cape Newagen north along the eastern side of the Sheepscot River to Fort Edgecomb.

Kidd says that over the years she has seen an increase in bird sightings near Carson's home at Lower Mark Island. "A lot of the herons and ospreys - birds affected by DDT - have come back," she says. "Rachel would be very happy about that."

Promoted as a miracle insecticide that was harmless to humans, DDT was invented in 1939 and used to kill disease-spreading insects. Long concerned about the dangers of unregulated pesticides, Carson set out to prove that claims coming from government and industry were misguided, designed to lull the public to sleep. In 1958, Olga Huskins, a friend and Roxbury, Massachusetts resident wrote to Carson asking for contacts in Washington she could complain to about the indiscriminate aerial spraying of DDT mixed with fuel oil over her residential neighborhood. A mosquito control plane hired by the state had begun crisscrossing Hutchins neighborhood near salt marshes, leaving in its wake the corpses of songbirds, honeybees and harmless insects.

With encouragement from New England writers like Edwin Way Teale, the naturalist, and E.B. White, Carson spent the next five years writing what would become one of the most important books of the century. Published 40 years ago, Silent Spring became a best seller even before it was released. The following year, President Kennedy's Science Advisory Committee issued a report calling for more research into the potential health hazards of pesticides and warning against their indiscriminate use. In 1964, Carson died after a long battle with cancer.

Before her death, Carson wrote to her friend and Maine neighbor, Dorothy Freeman, to say she didn't think she would live to see another migration of monarch butterflies. Come every October, Ward Feurt, the refuge manager at the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in Wells, looks out his office window and sees "a stream of orange and black wings fluttering unevenly along the Carson Trail." He walks the mile-long trail almost every day. Of the nearly 350,000 visitors to the refuge each year, about 100,000 walk the trail, he says. They leave behind notes like "Rachel Carson would be proud," "Best nature trail ever," and "A gift from God." As is true throughout the refuge, no pesticides are used along the trail to control vegetation.

Named in honor of Carson in 1970 the refuge covers more than 5,000 acres, along 50 miles of southern Maine's coast. "People come here from all over just because of the refuge's name," Feurt says. "To many it's like a pilgrimage. Carson inspired so many."

With those thoughts in mind, we dedicate this issue of the Gulf of Maine Times to Carson's memory and her continuing legacy four decades after the publication of Silent Spring. Each spring the Times highlights people around the Gulf who likewise display an intense vitality and quality of engagement and commitment to safeguarding the health and future of our coastal watersheds. Collectively, the individuals who received the 2001 Gulf of Maine Council's stewardship awards are working to restore salt marshes and habitat, protect marine mammals and shorebirds, save precious coastal lands, bridge cultures, extol the glories of a river's heritage and use new technologies to help repair coastal environmental damage.

And the work continues. As Lee Bumsted reports, a dedicated group of stewards are planning to kayak the Gulf of Maine this summer on a mission to educate and inform the public about the Gulf, with ten stops along the Cape Cod to the Bay of Fundy route. Like the return of the herons and ospreys to Lower Mark Island, Carson would also be pleased to know that countless others have embraced her message and are carrying forth the torch.