Science Insights: Ecosystem-based management: moving from concept to practice

Printer Friendly Page

By Peter H. Taylor

|

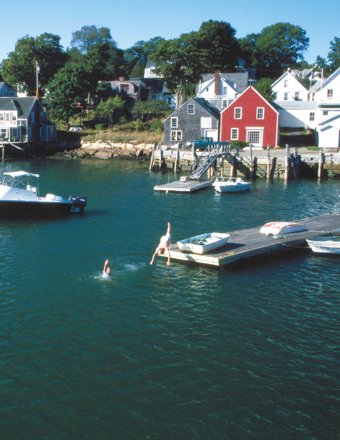

PHOTO: PETER TAYLOR |

It's not an easy issue. How should ecosystem-based management (EBM) be put into practice? The groundswell for this new approach for coastal and ocean management has been building for more than a decade.

EBM is an innovative management approach that considers all ecosystem components, including humans and the environment, instead of managing one issue or resource in isolation (see http://www.ebmtools.org). Many other names exist for essentially the same concept, such as the ecosystem approach to management, integrated multi-use ocean management, and strategic-habitat conservation.

Calls for a new approach to ocean management stem from the failure of traditional approaches, which focus on single issues and resources, to sustain a healthy ocean. Despite the labors of many people in government agencies, the ocean is chronically ill and getting worse. The spectacular collapse of the Gulf of Maine region's cod fishery is presented in classrooms across North America as a prime example of how the old management practices failed.

A turning point

Now is a critical turning point for EBM. In the past few years, managers, scientists, and policymakers have participated in countless meetings and read stacks of reports on EBM. Many people agree that EBM is a good conceptual framework and that it is a promising direction for coastal and ocean management. Others do not. Some questions remain unresolved. For example, what does EBM mean in practice? How do we do it? What needs to be done in specific terms to implement EBM in the Gulf of Maine?

Will today's wave of support for EBM disappear as managers and policymakers grow weary of trying to figure out how to do it? Or will we ride the EBM wave into a more successful era of coastal and ocean management? Right now, there's a real danger of the former, but plenty of potential for the latter.

EBM is a concept that developed and coalesced over a number of years, mostly in academia. Today the big challenge is to transfer EBM ideas from the language of academia to the practice of on-the-ground resource management and governance. Broad visions of EBM must be embodied in policies, objectives, procedures, and tasks for government agencies and non-government conservation partners. What's needed is a concerted effort to evolve from generalized discussion to actual EBM activities grounded in the complexities of a real place, such as the Gulf of Maine.

Are EBM principles being adopted?

Three articles published recently in Science and Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment offer some guideposts for people trying to move EBM from theory to practice.

In the December 2006 issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, Katie Arkema, Sarah Abramson, and Bryan Dewsbury investigated whether EBM principles are being adopted in management practices.

Ecosystem-based management is an innovative management approach that considers all ecosystem components, including humans and the environment, instead of managing one issue or resource in isolation. |

In the scientific literature, Arkema and her co-authors identified 17 criteria used to characterize EBM. Three general criteria deal with sustainability, ecological health, and inclusion of humans in the ecosystem. Fourteen specific criteria focus on ecological, human, and management dimensions.

Ocean and coastal management plans examined by Arkema and her co-authors fell short of meeting the criteria for EBM. The plans fulfilled some of the general criteria, but rarely addressed the specific criteria. For example, few of the plans adequately considered ecological criteria regarding ecosystem complexity, temporal scales, and spatial scales.

The study concluded that specific EBM criteria are lost in the transition from definitions to objectives to management actions. “Scientists characterize EBM differently than agencies planning to manage coastal and marine ecosystems. We found that management objectives and interventions tend to miss critical ecological and human factors emphasized in the academic literature,” the authors wrote. “Our results indicate that managers are beginning to put some EBM principles into practice, but this implementation needs to be much greater” for EBM to be fully realized.

The core challenge is that EBM emerged from the academic world, where generalization, theory, objectivity, and taking the long view are highly valued. Putting it into practice will involve developing concrete approaches to implementation that are specific, pragmatic, politically palatable, and achieve results.

Umbrella goal: protect biodiversity

Seafood production, climate regulation, water filtering, and other valuable functions of ecosystems represent a common focus for scientists and managers. Sustaining such ecosystem services, which have economic value and attract support from the public, is the umbrella goal for EBM.

Simply put, the way to sustain ecosystem services on a regional scale is to protect biodiversity. A paper called “Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services” in the Nov. 2, 2006, issue of Science made this plain. Boris Worm and several co-authors found that losses of regional biodiversity in the ocean “impaired at least three critical ecosystem services: number of viable (noncollapsed) fisheries; provision of nursery habitats such as oyster reefs, seagrass beds, and wetlands; and filtering and detoxification services provided by suspension feeders, submerged vegetation, and wetlands.” The study concluded that substantial loss of biodiversity is closely associated with the regional loss of ecosystem services. Guarding against loss of biodiversity is a linchpin of EBM.

Priorities: threats to biodiversity

To protect biodiversity, the practice of EBM needs to focus on fishing, harvesting, and protecting and restoring habitats, according to a paper in the June 23, 2006, issue of Science. The paper, “Depletion, Degradation, and Recovery Potential of Estuaries and Coastal Seas,” showed that these issues are the leading causes of species declines and extinctions. Included in the global study were two parts of the Gulf of Maine: the Bay of Fundy and Massachusetts Bay.

According to the study, fishing, harvesting, and habitat destruction often work synergistically to reduce biodiversity, while other factors such as pollution, eutrophication, and invasive species play smaller roles. Reducing the cumulative impacts of these stressors through an integrative management approach can promote species recovery. The scientists found that only 22 percent of species recoveries resulted from the mitigation of a single human impact, while 78 percent resulted from reduction of at least two impacts. They concluded, the “cumulative effects of multiple human interventions must be included in both management and conservation strategies.”

Moving forward

EBM Newsletter A new email newsletter is being launched to share news, analysis, and thought-provoking points of view about EBM in the Gulf of Maine. For a free subscription to the newsletter or to contribute information, contact Peter Taylor at gulfofmaine@ecosystembasedmanagement.net |

The following step-by-step examination could help move EBM from concept to practice in the Gulf of Maine. The ideas are based on discussions with people around the region, including participants in an EBM workshop held in March at the University of New Hampshire (http://www.gulfofmaine.org/ebm/meeting2007).

- Retrospective case studies from the region: Science-based discussions of scenarios in which a non-EBM approach was used without success. How could it have been done differently and more effectively with EBM?

- Present-day case studies: Science-based discussions of specific management challenges facing the Gulf of Maine and its watershed. What might the solution be in the context of EBM?

- Scientific consensus statement on regional priorities: What are the most important issues in the Gulf of Maine? What issues absorb more management effort than deserved from an ecological standpoint?

- Examples of activities that are and are not EBM: A clear-eyed look at management activities in the region that embody EBM and those that don't.

The paradigm shift in progress toward EBM is a good example of the old saying that nothing worthwhile is easy. But if EBM can be done anywhere in the world's oceans, it ought to be the Gulf of Maine.

Peter H. Taylor is a consultant for the Gulf of Maine Science Translation Project. For more information see www.gulfofmaine.org/science_translation.

© 2007 The Gulf of Maine Times