![]()

Volume 6, No. 4

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

Browse the archive |

|

|

|

|

Science Insights

The silencing of the loons?

By Ethan Nedeau

Years ago I sat on a remote island in Maine and watched the moon rise over Baskahegan Lake. The moon, stars and satellites were the only lights from the land or sky, and the only sounds were a quartet of loons. I listened for hours, marveling at their haunting cries, and reflected on the times I had spent near lakes and loons. Now an environmental scientist, I recall that evening with some sadness because I am more aware of the invisible threats to loons in the Northeast. Loons may not be as timeless as the lakes they inhabit, and it is possible that someday, special places like Baskahegan Lake could fall silent.

Throughout North America, air-and-land-derived pollutants inflict serious damage to aquatic ecosystems, and in the Gulf of Maine region a pollutant of great concern is mercury. Even in small doses it can cause serious health problems and even death in wildlife and humans. Although mercury occurs naturally, humans have greatly increased its availability in the environment. Scientists estimate that two-thirds of global mercury emissions are from human sources, such as metal manufacturing, fossil fuel combustion and waste incineration. In northeastern North America, air-derived mercury reaches the landscape at rates two to four times higher than prior to the Industrial Revolution.

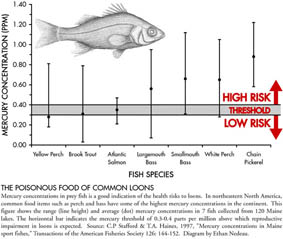

Most atmospheric mercury is in an inorganic form that is only mildly toxic at low doses. But when inorganic mercury reaches freshwater or marine environments, it can be converted into a toxic substance called methylmercury. Methylmercury enters the bodies of small aquatic organisms and is then passed to larger and larger predators in the food chain, in a process called biomagnification. Animals toward the top of the food chain–like large predatory fish such as largemouth bass and chain pickerel, fish eating birds such as loons and eagles, and mammals such as otters and seals–may end up with very high concentrations of mercury in their bodies.

Because of high levels of mercury in their tissue, freshwater fish in northeastern North America may pose a health risk to people or wildlife that consume them. This has prompted the United States and Canadian governments to establish consumption advisories for humans. Mercury is at least partially responsible for over 2,200 fish consumption advisories in over 40 states in the United States. According to a warning issued by the Maine Bureau of Health, pregnant and nursing women, women who may get pregnant and children under age 8 should not eat freshwater fish, except one meal per month of brook trout or landlocked salmon. People who consume more fish than what is recommended in those guidelines place themselves, their children, and their unborn fetuses at risk. The dangers include damage to the central nervous system, endocrine system, immune system and chromosomes. Fetuses face the highest risk because methylmercury concentrates in the developing brain, causing abnormalities that may lead to behavioral deficits, impaired fertility or death

|

|

|

Recent scientific research has focused on the effects of mercury on ecosystems and wildlife in the Gulf of Maine region. Maine is probably contributing more to this research than any state in the United States and much of this work can be attributed to David Evers, a research scientist who founded the BioDiversity Research Institute (www.briloon.org/) that specializes in the effects of mercury on wildlife, particularly loons.

Studies show that reproductive impairment usually occurs in lakes where mercury concentrations in prey fish exceed 0.3 to 0.4 parts per million. Up to 30 percent of Ontario lakes had fish in the preferred size range for loons whose mercury concentrations exceeded this threshold. Loons that consume mercury-contaminated fish accrue dangerous levels of mercury in their bodies, yet the effects of this poisoning are often very subtle and require careful observation to detect. The BioDiversity Research Institute has documented many such effects, including a higher incidence of unattended eggs, atypical incubation behavior and a reduction in foraging behavior. Other studies have documented behavioral changes in chicks, leading to poor nutrition and reduced fitness.

What is the overall effect of mercury on loon populations? Some evidence comes from lakes near Kejimkujik National Park in Nova Scotia, where loons have the highest blood mercury levels of any North American population. Reproductive output in these lakes has been reported to be 0.29 chicks per breeding pair, which is almost half of what is typical for this species (0.50 chicks per breeding pair) and well below what is needed to maintain a population. Similar results have been found throughout Maine, where David Evers summarized his research by saying, “The bottom line right now is that around one-third of Maine’s breeding loons are at risk and are producing 40 percent fewer fledged young that they would otherwise.” Models to predict the population-level consequences of this are currently being developed.

The existence of loons in the Gulf of Maine region may be in jeopardy, unless environmental regulations and public education can achieve significant reductions in mercury deposition. Identifying and controlling sources of mercury pollution is the most important action we can take to protect our lakes, their inhabitants, and ourselves. Much progress has been made to control mercury pollution at the local level through public education, recycling programs and promoting alternatives to mercury-containing household and industrial products. Yet atmospheric mercury coming from industrial areas in the central United States and Ontario remains a huge concern. We will need to target distant smokestacks if we are to curtail mercury pollution in our region. A lake without loons is like an ocean without whales or a night without stars. Hopefully we will not silence them forever.

Ethan Nedeau is a Science Translator for the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. He can be reached at ejnedeau@attbi.com