Despite rejections, LNG proposals move up the coast

Passamaquoddy Bay is no place for terminals, say opponents

By Maureen Kelly

Printer Friendly Page

The proposals follow several attempts by other developers to site LNG terminals in coastal Maine.

Over the past two years, Maine residents have rebuffed proposals in Harpswell, Cumberland, Yarmouth,

Gouldsboro and Searsport.

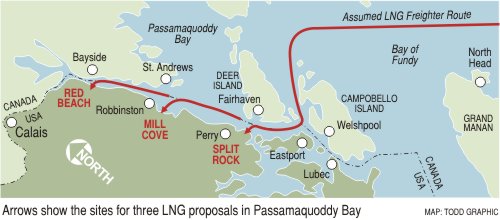

If approved in the Passamaquoddy region, the LNG facilities would be located on the U.S. shoreline

of the bay, which straddles the U.S./Canadian border. But since tankers making deliveries would have

to traverse Canadian waters to reach port, the Canadian government may ultimately determine whether

the American terminals are built.

Oklahoma-based Quoddy Bay LLC was the first to announce plans for a terminal on Passamaquoddy

tribal land that would include a pier with berths for two tankers and an eight-mile pipeline to

storage tanks in Robbinston, Maine. After residents in nearby Perry voted against the company's

proposal to site the facility at Gleason Cove last March, the company and tribal leaders reached

a controversial agreement in May for the lease of a site at Split Rock on the Pleasant Point

reservation.

Elsewhere in the Gulf of Maine, other energy companies are vying for approval to build terminals.

In Massachusetts, AES Corporation has proposed to build a facility in Boston Harbor on Outer Brewster

Island, part of a state and national park. Excelerate Energy and Neptune LNG are each planning

offshore terminals in federal waters off Massachusetts's North Shore.

Irving Oil and Repsol received approval from the Canadian government to jointly construct a

terminal in Saint John, New Brunswick, 60 miles from the U.S. border. The so-called Canaport

terminal will be operational by 2008 to serve the Canadian and U.S. markets. Canadian officials

consider Saint John a good location for the terminal since the city, home to an oil refinery, is

already industrialized, has infrastructure in place to minimize pollution and is on established

shipping routes.

Presently, the Distrigas terminal in Everett, Massachusetts, is the only LNG terminal in the

region, one of six in the United States.

Natural gas is contributing an ever larger share to New England's energy mix for heating homes

and generating electricity. Industry experts and public energy officials predict that demand will

soon outpace domestic supply and the region will need new sources of the fuel by the end of this

decade to reliably deliver during peak winter months. Liquid natural gas - imported from overseas,

gasified then shipped by pipeline to regional markets - is seen as one of the most viable options

for increasing supply. Natural gas is cleaner than other fossil fuels producing fewer greenhouse

gas emissions.

Yet opponents of the proposed projects believe that LNG's benefits are outweighed by the

potential for ecological and economic damage, and harm to humans that ships full of hazardous

cargo could present in the bay.

Hundreds of area residents participated in anti-LNG rallies and thousands signed petitions that

went to the government of Maine and the U.S. and Canadian federal governments, said Linda Godfrey,

coordinator of a cross-border grassroots organization, Save Passamaquoddy Bay. Several Canadian

politicians voiced opposition as well. In August, New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord announced

that he wanted the Canadian federal government to reject the American proposals. Canada could

deny tankers access to its waters, blocking their route to port, as the nation did thirty years

ago when it barred oil tankers from those same waters because of the high ecological value of

the area and navigational risk.

LNG tankers as long as three football fields will have to navigate through the Bay of

Fundy - renowned for its extreme tides and strong winds and currents - to Head Harbour Passage

where tugboats would escort the tankers for a two-hour inland voyage. The passage is deep but

narrow, which would require tankers to run close to the shoreline. The ships would also have to

avoid a natural hazard called the Old Sow Whirlpool, the second largest whirlpool in the world.

The Head Harbour area is a rich feeding ground for birds and wildlife drawn to the clusters of

plankton and krill that are abundant there. Harbor porpoises, basking sharks, seals and finback,

humpback and minke whales inhabit the area. Endangered North Atlantic right whales migrate to the

Bay of Fundy in the summer and near proposed routes and tend to concentrate in protected zones east

of Grand Manan Island.

The impacts of LNG tanker traffic on wildlife will be investigated as the companies move forward

with their environmental impact statements. The Canadian government will also conduct a comprehensive

study that will look at the biological, social and economic impacts of the projects on Canada, said

Greg Peacock, executive director of Provincial Relations at Canada's Department of Fisheries and

Oceans.

Concerns over the projects' impact on the local economy have surfaced on both sides of the

border. The bay's natural resources are the backbone of a $1 billion “eco-economy” that employs

thousands in the tourism, aquaculture and fishing industries, said Art MacKay, executive director

of the St. Croix Estuary Project in St. Stephen, New Brunswick. He believes the exclusion zones

that would surround tankers en route to the terminals would disrupt commerce in the bay and that

local business could lose million of dollars due to these downtimes.

On the American side, others worry about the cost local communities would have to bear to enhance

emergency response and infrastructure to support an influx of workers.

“It's going to be a huge burden on towns,” Godfrey said.

Opponents also point out that looking to the LNG industry for economic development seems

shortsighted to some who expect few jobs will be available to locals after construction.

If the terminals are built, the U.S. Coast Guard and Transport Canada would have to coordinate

security for tankers transiting between the two nations' waters.

Security measures requiring lights, gunboats, surveillance and citizen refuge areas would “take

away from everything this place is,” said Godfrey, who believes that LNG terminals should be sited

in already industrialized areas.

Within the next few months, Godfrey and others on both sides of the issue will find out if the

U.S. and Canadian federal governments agree with them.

THE DEBATE over the siting of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals has reached the northernmost

shores of Maine with three proposals to build terminals for offloading LNG from ships in the

deepwater ports of Passamaquoddy Bay. While the projects could provide a new source of energy

for New England and bring jobs to Maine's Washington County, opponents argue that an LNG terminal,

and the huge tankers that service it, will pose a threat to a vibrant coastal ecosystem and destroy

the region's tourist trade by industrializing small coastal communities, tribal lands and resort

towns. LNG terminals and their land-based facilities could also make the area vulnerable to terrorism

or an accidental spill, opponents say.

THE DEBATE over the siting of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals has reached the northernmost

shores of Maine with three proposals to build terminals for offloading LNG from ships in the

deepwater ports of Passamaquoddy Bay. While the projects could provide a new source of energy

for New England and bring jobs to Maine's Washington County, opponents argue that an LNG terminal,

and the huge tankers that service it, will pose a threat to a vibrant coastal ecosystem and destroy

the region's tourist trade by industrializing small coastal communities, tribal lands and resort

towns. LNG terminals and their land-based facilities could also make the area vulnerable to terrorism

or an accidental spill, opponents say.

Proposals in Maine and elsewhere

Washington D.C.-based Downeast LNG wants to build a terminal, including a pier and storage tank,

at Mill Cove in Robbinston. And Washington County-St. Croix Development, a locally-owned concern

founded by two Maine state representatives - one of whom represents the Passamaquoddy tribe - became

the third entity to propose a terminal in the bay, at the Red Beach section of Calais.

Washington D.C.-based Downeast LNG wants to build a terminal, including a pier and storage tank,

at Mill Cove in Robbinston. And Washington County-St. Croix Development, a locally-owned concern

founded by two Maine state representatives - one of whom represents the Passamaquoddy tribe - became

the third entity to propose a terminal in the bay, at the Red Beach section of Calais.

Increased demand

Impact on local economies

© 2005 The Gulf of Maine Times

LNG - natural gas cooled to its liquid state at -260o F (-162.2o C) - has been transported

across the world's oceans for over four decades. After delivery, LNG is either stored or heated

to turn it back into gas for delivery to homes and businesses.

LNG - natural gas cooled to its liquid state at -260o F (-162.2o C) - has been transported

across the world's oceans for over four decades. After delivery, LNG is either stored or heated

to turn it back into gas for delivery to homes and businesses.