![]()

Volume 7, No. 1

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

Browse the archive |

|

|

|

|

Eyes on the future

The 2002 Gulf of Maine Council Visionary Awards honor individual stewards and nonprofit organizations that have demonstrated extraordinary effort and innovation in caring for the Gulf of Maine watershed.

By Andi Rierden, Editor

Dr. Moira Brown

Provincetown,

Massachusetts

|

| Dr. Moira “Moe” Brown Photo: M. Sironi |

A senior researcher for the Center for Coastal Studies, the co-chair of the Canadian Right Whale Implementation Team and one of the founders of the Atlantic Right Whale Disentanglement Team, Brown has spent the past 20 years working to protect the mammal - the most endangered large whale on Earth. She collaborates with an international consortium of researchers to develop whale-watching technology and modify fishing equipment to reduce the number of whale injuries and deaths. By photographing the backs of the whales, Brown and other scientists have found that two-thirds are scarred from collisions with ships and struggles with fishing gear.

Born in Montreal, Brown studied with Dr. David Gaskin, the founder of the Whale and Sea Bird Research Station on Grand Manan. In 1985, she founded East Coast Ecosystems, a right whale conservation organization based in Freeport, Nova Scotia. Brown says she applauds the decision to make the waters safer for the whales, adding, “There was some cost to the Nova Scotia fishermen who lost access to some bottom [fishing ground] with the shift, but they recognized the conservation importance to right whales.”

Amy Holt Cline, Charles Saulnier, Steve Chinosi, George Vanikiotis

Essex Agricultural and Technical High School, Danvers, Massachusetts

|

| Amy Holt Cline and Charles Saulnier (standing) with students Photo: Laura Marron |

This blend of technology, canoe building, marine and inland biology and literature is meant to be a refreshing departure from the textbook approach to teaching, says Saulnier, adding, “With biology everything is taught in isolation. We wanted to change that.” To broaden the students’ scope, the educators supervise field trips to Nova Scotia where students meet with fisheries and GIS experts, tour a lobster pound and join other students in Clare to learn how to grow and release salmon into the wild. “We felt that these kids should know something about their closest foreign neighbor and benefit from knowing what we all share living around the Gulf of Maine,” Saulnier says.

Ted Regan and Aaron Frederick

Portland, Maine

| Ted Regan (left) and Aaron Frederick Photo courtesy of Ted Regan |

The concept was born in 1999, when Regan, Frederick and four team members kayaked from Lubec, Maine to Key West, Florida to pay tribute to the lives of several people, and friends of Regan, that had died of AIDS. The journey was part homage to his friends and part AIDS prevention education, says Regan, who organized the expedition. After kayaking 2,700 miles and meeting with 2,300 youngsters in ports along the eastern U.S. seaboard, Rippleffect returned to Maine and revised its mission.

Today Rippleffect runs programs along the Portland waterfront where participants explore sea kayaking fundamentals and the history and environment of Casco Bay. Two years ago, the organization raised the funding necessary to purchase the 26-acre Cow Island in Casco Bay, with assistance from the Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Rippleffect has since created the Cow Island Ocean Academy, offering youngsters week-long adventures in sea kayaking skills, island geology and culture.

Outreach & Education Committee

City of Dover, New Hampshire

|

| “Growing Greener” workshop organizers (from left to right): Cheryl Bucklin Niles, Anna Boudreau, Tom Fargo, Joyce El Kouarti, Wendy Scribner. Photo: Chris Fargo |

Within weeks of the workshops, the City’s planning board voted to change the zoning regulations to manage residential growth and protect natural resources. Not only that, says says Joyce El Kouarti, the Outreach & Education Committee’s chair, land conservationists and the business sector are pursuing joint initiatives to preserve open space and control development. Several landowners have also contacted the committee seeking more information about land conservation. “You never dream that [rapid growth] is coming to your community,” El Kouarti says. “You think that the farm down the road will stay this way forever. Then the farmer dies, his son sells the land and all of the sudden there’s a subdivision. That’s the reality.”

Barbara Baird

Greenland, New Hampshire

|

| Barbara Baird Photo courtesy of Ann Reid |

“Since I grew up on the bay, I had a lot of concerns especially about the declining eel grass,” she said. “Then I started with the Great Bay program and just got wrapped up in it.”

Baird monitors at the entrance of the Winniconic River near Greenland, downstream from a golf course. “We get a lot of run-off from animals upstream and extra nutrients from the golf course,” she says. “But it’s not out of line.” Baird has trained and educated dozens of volunteers over the years with an emphasis on how important their data is to different government agencies and communities.

Not one to crowd the limelight, Baird says, “The Great Bay Coast Watch is an important program and it’s made up of a lot more people than just me. They all deserve credit.”

Atlantic Salmon Federation

St. Andrews, New Brunswick

|

| A snapshot of the ASF’s Fish Friends Courtesy of Atlantic Salmon Federation |

In the Gulf of Maine region, ASF was a major partner in removing the Edward’s Dam on the Kennebec River in 1998, and was instrumental in efforts to list Maine’s Atlantic salmon as endangered in 2000 and inner Bay of Fundy salmon as endangered in 2001.

On the Magaguadavic River in New Brunswick, ASF tracks interactions among wild and escaped farmed salmon and is working on a recovery program for the river. ASF scientists have also developed an innovative tagging system that follows smolts into the ocean in hopes of identifying the places where they are dying.

Each year hundreds of schools through out New England and Atlantic Canada participate in Fish Friends, an interactive classroom program where students raise Atlantic salmon or trout to fry stage and release them into streams.

On the international front, ASF works to safeguard the wild fish throughout its range. At the urging of ASF, government officials and other salmon conservationists, Greenland’s fishermen recently agreed to end the last commercial fishery that targeted the North American wild salmon. Bill Taylor, ASF president, said the suspension should bolster salmon restoration efforts throughout the North Atlantic. “I don’t want anyone to think that next year our rivers will be full of fish,” Taylor said of the Greenland agreement, “But we’ll definitely see more fish returning.”

Dr. Martin Willison

Halifax, Nova Scotia

|

| Dr. Martin Willison Photo courtesy of Martin Willison |

As an educator and president of the Nova Scotia chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Willison refers to marine conservation areas as “biodiversity insurance schemes” that will act as “seed banks” for the future. He adds, “Biodiversity conservation is not just an academic discipline, but a moral and political foundation for society.”

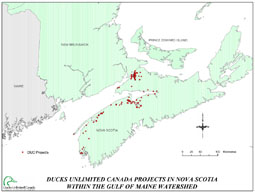

Ducks Unlimited Canada

Amherst, Nova Scotia

|

| Ducks Unlimited Canada map of more than 50 completed projects in Nova Scotia Courtesy of John Wile, Ducks Unlimited Canada Click on the picture to enlarge |

Over the years, DU has expanded its focus and now conserves wetland habitats by managing entire landscapes instead of individual wetlands. The Belleisle Marsh Project in Annapolis County is one an example where DU has integrated wildlife habitat needs into a working agricultural landscape.

Today DU, working with other partners, offers a wide range of programs to landowners including restoring or enhancing wetlands, livestock fencing to restore riparian buffers, soil conservation and wastewater management.

DU recently built two large “constructed” wetlands that provide wildlife habitat and serve as tertiary wastewater treatment systems for the town of Annapolis Royal and for the Village of River Hebert. Both communities are situated along Bay of Fundy tidal rivers.

“Knowing how wetlands and riparian habitats filter and purify water, we feel that our programs to conserve wetlands are contributing towards a healthier and more sustainable Gulf of Maine, but we also realize that we have much more work to do before we are finished,” Wile says.

David A. Ganong

St. Stephen, New Brunswick

|

| David A. Ganong Courtesy of Ganong Brothers, Limited |

These words, spoken in 1987 by Whidden Ganong, of the Ganong chocolate-making family, describe an extraordinary coastal headland that separates the St. Croix Estuary from Oak Bay near St. Stephen. Whidden and his wife, Eleanor, purchased the property in 1951. Before his death in 2000, at the age of 93, Whidden specified in his will that the property be turned into a nature park. His nephew, David A. Ganong, the president of the Ganong Bros. Limited, fulfilled the dream of his uncle by championing the idea that the property be enjoyed in perpetuity by New Brunswickers and visitors. He facilitated the transfer of the family-owned lands into a conservation trust managed by the St. Croix Estuary Project (SCEP).

The Whidden and Eleanor Ganong Nature Park contains 330 acres [142 hectares] of diverse shoreline, rolling fields, a granite outlook with a spectacular view, intertidal land, gardens and an orchard. The community-owned marine park opened officially in June.