![]()

Volume 6, No. 2

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

||||||||||

|

Regular columns |

|

Archives |

|

About |

Bay of Fundy forums designed to motivate

In a recent essay in National Geographic Magazine, E.O. Wilson, the Harvard University biologist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner paints a sobering world review: "Our species, at more than six billion strong and heading toward nine billion by mid-century, has become a geophysical force more destructive than storms and droughts. Half the world's forests are gone...Polluting, damming, and the introduction of alien organisms are causing the wholesale extinction of native aquatic species...Many experts believe that at the present rate of environmental change, half the world's surviving species could be gone by the end of the century."

Key to rescuing these fragile areas is a push by conservation groups and scientists to work closely with governments, businesses and the local citizens that depend upon these lands or seas for their economic survival. As an accompanying article makes clear, building bridges is not easy, yet good protection and good science can and do combine forces to manage healthy ecosystems.

"We want to motivate communities to identify key issues, come up with a plan and then help them carry out doable projects," she said.

If we consider our own corner of the world here in the Gulf of Maine, the Minas Basin would surely be among its hotspots. Located in the upper reaches of the Bay of Fundy, the Basin is world-renowned for its geology and geometry. Its arrow shape together with the surging waters of the whole Bay produce the highest average tides in the world. More than 30 rivers flow into its cavity, feeding in sediment and creating an intricate and complex dynamic. The Basin's mudflats, which fan out at low tide like an intertidal prairie, are a magnet for waterfowl and shorebirds that congregate in massive flocks. The long-legged sandpipers and plovers, in particular, draw birders and conservationists from every part of the globe.

Despite its relative remoteness, the Minas Basin is under great stress. Development mostly in the eastern side in Kings County threatens wetlands, water quality and wildlife habitat. A declining and increasingly corporate-owned fishery drains the economic viability of small communities. Decades of poor forestry practices, outdated septic systems and agricultural run-off have degraded rivers and streams.

By April, forums held in Wolfville, Truro and Parrsboro had drawn nearly 400 people. The Parrsboro forum drew the largest crowd of 200 people plus, with many eager to vent their sometimes conflicting and impassioned concerns. In the opening segment, some attendees said they wanted more conservation measures, while other residents, some representing ATV or snowmobile associations, were adamant, saying that the new provincial park at Cape Chignecto¾where motorized recreational vehicles are prohibited¾and a proposed conservation reserve for the Upper Bay of Fundy were conspiring to destroy a way of life they had known for generations.

Hoping to clear up the confusion about a range of land-based issues in the region, Terry Nutthall, her father Art Fillmore and other residents had formed the Conservation Study Group. "We've got so many groups bombarding us with information," Fillmore said. "We're here to try to get some answers."

Chester McBurnie, 74 years old, sat next to his wife Marilyn and his two sisters. His agenda was agriculture. "I've been getting up all my life seven days a week and taking care of my farm that's been in my family five generations. Now they want us to fence off the brooks so the cows can't get in them. Well, those cows have been going into those brooks all along and they haven't killed anybody yet, so what's the point?"

In a separate focus group, people voiced their worries about overfishing and the destruction caused by fishing gear. "The draggers come through and then there's not a fish left," one weir fisheman said. "Some of these boats with satellite [equipment] will go in and take whole schools of fish and there's not enough officers to enforce things."

Another group discussed potential effects of pharmaceuticals spilling into waterways and the "chemical rain" coming from parts of the U.S. Midwest and southern Ontario. "We always think about saving the planet for the next generation," said a schoolteacher. "But with all the destruction humans are causing, we better start thinking about saving the species, period."

The forums did generate a range of potential solutions and actions, from lobbying for more effective policies and legislation to education campaigns.

Yet with so many problems and different viewpoints, not to mention the many competing pressures on natural resources, and with government itself often divided as to how those resources should be allocated, what, I wondered, can a few citizens really accomplish? BoFEP's answer is to ferret out community leaders at these meetings, continue discussions in smaller venues, attract funding, build alliances, then help them walk the talk.

It is a good, positive plan.

The grand conundrum of trying to balance conservation with economic needs and cultural traditions won't happen overnight, but as these forums made clear, there are many citizens straddled with a loss of certainty and feelings of powerlessness who are willing to give it a try.

As one retired fisherman told another on the way out to the parking lot, "Part of me thinks it's a waste of time, but if we don't start talking out our differences and figuring out what to do, it'll all go to hell."

A promising glow in this warren of destruction, Wilson continues, are the 25 "hotspots" that conservation biologists define as "highly threatened but fertile grounds." Together, these hotspots, ranging from the Caribbean to the Western Ghats in India, contain more than 60 percent of the world's plant and animal species¾within just 1.4 percent of the planet's land surface. British ecologist Norman Myers developed the hotspot concept in 1988, and his analysis has been adopted by conservation organizations internationally.

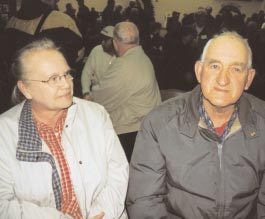

Art Fillmore and daughter Terry Nuttall, say they've been bombarded with information and came to seek some truth. Photo: Andi Rierden

Closer to home, the obstacles and promises of a shared approach to natural resource management and sustainability are being played out in communities throughout the Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy. One recent example was a series of public forums held this spring by the Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership (BoFEP), a Fundy-wide conservation and research group, and local hosts. Their aim, according to forum organizer, Robin Musselman, was to encourage community awareness of the natural and human resources of the Minas Basin watershed and to begin action toward their sustainable management.

Chester and Marilyn McBurnie say they are tired of being "regulated to death."

Photo: Andi Rierden