![]()

Volume 6, No. 2

Promoting Cooperation to Maintain and Enhance

Environmental Quality in the Gulf of Maine

|

||||||||||

|

Regular columns |

|

Archives |

|

About |

Global warming in a Maine estuary

By Ed Myers

Way back in the month of March, 1917 (only coincidentally the month and year of this columist's birth), father and son Evander and Ervine Hatch slid a building for the Bristol Ice Company off the wharf and onto the ice in Clark's Cove, Maine. They trigged a capstan out ahead of it and moved the structure across the Damariscotta River with capstan bars and six-part blocks. The job took most of a month, but there was no hurry because the salt water ice was over three feet thick. The building is still there in Edgecomb and is used to store farm equipment.

In the winter of 1971, we noticed that we had forgotten to remove the nice piece of nylon from a mooring stump about 150 yards from the dock. We strolled out confidently over the two feet of ice, removed the pickup buoy and the mooring line and put them in covered storage where they belonged, until spring.

In 1974, Clarks Cove had the beginnings of the first mussel farm in North America. In the ensuing 18 winters we used a scow-mounted plough blade to break ice from Clarks Cove, so that the floatation bottles for the mussel lines and the head-ropes would not be carried away. In the worst winter, we used up 17 full day's work on this chore.

There has been no ice whatsoever since 1993, when there were a couple of one-inch skims that went out on their own. The decade of the 90s is in the records as the warmest on the planet since data were collected, so it isn't all that surprising. When icebergs the size of Connecticut have broken off the Larsen B Ice Sheet in Antarctica and the Arctic has lost 42 percent of its cover, some effect can be expected from the Labrador Current on the Gulf of Maine.

In 1997, we had a casual visitor from Detroit who was employed by one of the automobile companies with membership in the Global Climate Coalition. Despite the sonorous title, this is the outfit financed by the coal and petroleum interests. Three of its "scientists" were taken to court in 1997 and under oath revealed fees of a $100,000 a year each for three years to debunk climate change and keep the issue "up in the air" (if you'll pardon the expression). We heard the man out as politely as possible, resisted saying anything pertinent and waved goodbye. Then we looked up March for the first four years in the 1980s¾the range was from 32 to 35.5 degrees Fahrenheit [0 to 2 C]. For 2002, the average was 40 F [10 C] in Clarks Cove. These are sea water temperatures, most generally a couple of degrees lower than the automated readings from the Large Navigation Buoy off Portland with temperature readings closest to us.

The World Almanac tells us that the United State's annual contribution to greenhouse gases is 4.1 billion tons. Lester Brown's latest book, Eco-Economy: Building an Economy for the Earth tells us that the United States alone sends enough into the atmosphere to warm the planet. The Worldwatch Institute's State of the World 2002 reaffirms that the eight major polluters following you know whom are all in the Northern Hemisphere. Philip Conkling of the Island Institute here in Maine traced Robert Peary's 1909 dog-sled tracks to the North Pole¾in a ship last summer. Bob Reiss in The Coming Storm tells us that there are ten trillion tons of methyl hydrates and methane waiting to melt as soon as the carbon dioxide load in the atmosphere takes the temperature up enough to get that going¾it is already started in parts of Siberia and Alaska, and if the permafrost ain't perma our abacus tells us that's four pounds of methane for every square foot of the planet's surface. The green crab and the sea squirt, scourge of bivalve seed and weighty competitor on bivalve lines respectively, have made their way up the Nova Scotia coast and turned the corner to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Research can be terrifying fun, but all we had to do this past winter for ground truth (or liquid truth) was go to the dock shed and look out the window.

Ed Myers is a columnist for The Working Waterfront, published monthly by the Island Institute. He lives in Damariscotta not far from Clarks Cove.

In March of 1944, Harry Marr's shipyard in Damariscotta (now the municipal parking lot) had two 93-foot wooden minesweepers ready to go to the Pacific. The Coast

Guard sent an icebreaker from Boothbay Harbor to carve out a channel for the vessels. As they set out on their long voyage, 50 or 60 cars and pickup trucks drove onto the two-plus- foot thick ice and drove alongside the minesweepers to keep them company as far as Cottage Point, horns blaring all along.

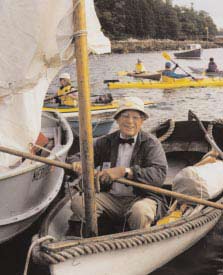

Ed Myers

Photo: Lee Bumsted