|

Off Limits: Inside the Gulf of Maine

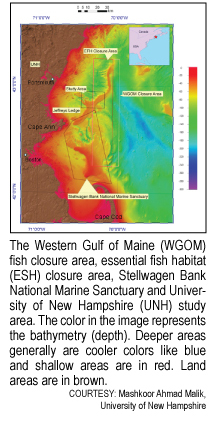

Closure Area

By Kirsten Weir

[printer friendly page]

Untold generations of New England

fishermen have made their livings in the fish-rich waters of

Jeffrey’s Ledge. Left behind by a glacier at the end of

the ice age, the rocky ledge roughly parallels the coast for

33 miles or 53 kilometers from Massachusetts to Maine. The ledge

itself is relatively shallow, but its edges drop off sharply.

At these margins, currents well up from the depths, carrying

nutrients that fuel a diverse marine ecosystem.

Over the last decade, however,

tightened fishing regulations have placed much of this storied

ledge off-limits to commercial fishermen. Now, scientists and

fisheries managers are taking a careful look at the Western Gulf

of Maine Closure Area, hoping to understand how it has affected

both the fishing industry and the ecosystem. In March 2007, scientists,

regulators, fishermen and others met at a symposium at the University

of New Hampshire (UNH) to discuss the effects of the closure.

The number of cod in the Gulf

of Maine plummeted by nearly half from 1986 to 1996. Hoping to

stem the crisis, the New England Fishery Management Council implemented

a number of regulations, from increasing the size of mesh used

in nets to limiting the number of days fishermen could spend

at sea. In 1998, the Management Council created the Western Gulf

of Maine Closure Area. The 1,100-square-mile (2,849-square-kilometer)

zone, containing much of Jeffrey’s Ledge, was closed to

commercial groundfishing.

Habitat

protection Habitat

protection

Initially, the closure was established simply to reduce the number

of cod being caught, Tom Nies, a senior fishery analyst at the

Management Council, told the symposium audience. “It was

chosen to be closed because people were catching a lot of fish

there,” he said. The Council’s original plan was to

shut the area for three years. But over the years, a series of

amendments extended the closure indefinitely and added an explicit

habitat-protection component as well. The Western Gulf of Maine

Closure Area’s goals now include protecting essential fish

habitat in addition to allowing cod stocks to rebuild.

Nine years after the closure

area was established, scientists are beginning to understand

the effects it has had on the habitat and the fishery. But piecing

together the puzzle is no small task. Possible effects of the

closure are confusingly intertwined with the effects of regulations

on net mesh sizes, days-at-sea limitations and catch limits.

Also, as Gulf of Maine Research Institute scientist Jonathan

Grabowski pointed out, no detailed baseline studies were done

before the area was closed. Scientists can compare habitat inside

and outside the closure, but they can’t compare present

conditions there to those of the recent past.

Still, scientists are starting

to draw some broad conclusions. For instance, UNH zoologist Ray

Grizzle found that on the rocky seafloor habitat common to Jeffrey’s

Ledge, invertebrate creatures such as sea squirts, sponges and

anemones were more abundant inside the closure than just outside

it.

“There’s a basic understanding

that the habitats are recovering,” Grabowski explained in

an interview. Still, it’s not clear how that recovery is

affecting cod and other commercially important groundfish. He’s

studied how the closure may affect juvenile fish. In general,

he said, juvenile groundfish tend to hang out in structured habitat,

the gravely bottoms and rocky ledges where they can hide from

predators and forage for food. But the link between seafloor

recovery and the health of groundfish populations isn’t

straightforward. In separate studies, both Grizzle and Grabowski

caught cod inside the closure area, but they both hauled in fewer

juveniles than they expected to find.

Impact on adult groundfish

Other researchers have focused on adult fish. Recent studies

have suggested the closure area has had little impact on the

movement patterns of adult groundfish in the region. Cod in particular

are very mobile and may not be spending enough time inside the

closure area to reap the benefits of protection.

While the jury is still out on

whether cod benefit from the closure, evidence suggests that

local fishermen may not. At the UNH symposium, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology anthropologist Madeline Hall-Arber said

she has found that increasingly strict fishing regulations have

created hardships for the owners of small vessels, and placing

much of Jeffrey’s Ledge off-limits has affected the way

many have fished for generations. For example, she said, the

closure has encouraged small boats to fish farther offshore than

is safe for vessels of their size.

Hall-Arber said many fishermen

recognize the importance of rebuilding the fish populations,

but they’d like to be sure that the regulatory red tape

is having a positive impact. When it comes to the closure area,

it may be a while before the picture is clear. Researchers agree

that more work is needed to understand the closure’s impact.

For now, it remains closed indefinitely.

“You can often document

changes in the habitat. You can see more things growing on the

bottom, more diversity of species,” Nies of the New England

Fisheries Management Council said in an interview. “The

big question that is hard to unravel is ‘What does it do

to the [groundfish] resource as a whole?’ Quite honestly,

I think it’s going to take time to figure out the answers.”

Kirsten Weir is a free-lance writer in Saco, Maine, who focuses

on science, health, and the environment.

|

![]()