|

Ambassador for his species: Ambassador for his species:

If a whale could speak

By Cathy Coletti

[printer friendly page]

“Do you know you hit a whale?!”

shouted my mother from the side of the Atlantic Queen about 20

miles (32 kilometers) offshore in the Gulf of Maine. The upswell

of anger ran through this group of about 60 whale watchers like

electricity.

It was one of those days you

hope will never happen again. Too many circumstances had come

together, too many things that are unknowable and unplannable.

The seas were calm. The sun was out. Visibility was perfect.

The cool ocean air smelled of salt. My mother was meeting my

little sister from Big Brothers Big Sisters after about a year

of trying to get a mutually agreeable date. The three of us were

out on Jeffrey’s Ledge in the Gulf of Maine in mid July,

seeing whale after whale.

I had been afraid that we might

be disappointed and not see anything. At first my little sister,

10, and I kept imagining that we saw whales, “What’s

that?” “Over there!” but it would turn out to

be just the way the sun hit the water or a buoy. Then she pointed

to the front of the boat and yelled, “WHALE!” People

rushed forward to see as the boat came to a stop.

From above, our naturalist, Jen

Kennedy from the Blue Ocean Society for Marine Conservation,

a New Hampshire-based nonprofit, informed us it was a “minke

whale.” Our luck held with more minke whale sightings and

then a fin whale sighting, an endangered species that is nothing

to snuff at: it’s the second-largest animal on earth, second

only to the blue whale. At up to 70-feet (21-meters) long, it’s

about as big as 13 human adults laid head to feet.

An

uncommon sighting An

uncommon sighting

Towards the end of the day on our way back to Rye Harbor, New

Hampshire, the Atlantic Queen came to a halt once again. It was

a fin whale. The spout rose above the ocean as the whale surfaced

to breathe, showing us its shiny black back. We were told that

we were only seeing a very small part of the gigantic body. What

a great ending to the day, or so we thought.

When a small sport boat came

out of the corner of my peripheral vision I thought, “Geez,

that guy is getting awfully close to that whale.” The loudspeaker

said, “This boater is not obeying whale watch regulations.

He’s way too close.” Then he went right over the place

where we had last seen the whale surface.

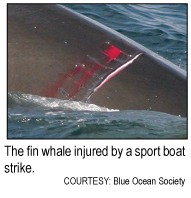

When the whale came up again,

bleeding slash marks were clear on the shiny black skin. There

was a silence, and then Kennedy’s voice over the loudspeaker,

“Never in my 12 years of whale watching experience have

I ever seen this happen.”

My little sister said she felt

sad. The crowd seemed shocked and then angry. As the Atlantic

Queen pulled up alongside of the sport boat to get documentation

for the authorities, my mother yelled, “Do you know you

hit a whale?” The boat’s operator didn’t respond.

Sharing the waters

What a sobering reminder that we share our ocean. As I sat with

the reporter from Fosters Daily Democrat, I told her

about how I would like to see this fin whale be an ambassador

for his species. That through press coverage and word of mouth,

the whale could simply tell us “Slow the heck down out there

and watch out, we’re here too!”

It

was prime boating season, which also coincides with the movement

of fin, humpback, minke and other whale and dolphin species,

which come to the Gulf of Maine to feed on schooling fish and

krill. It

was prime boating season, which also coincides with the movement

of fin, humpback, minke and other whale and dolphin species,

which come to the Gulf of Maine to feed on schooling fish and

krill.

Harming an endangered species

of whale is a violation of both the Marine Mammal Protection

Act and the Endangered Species Act, with fines of up to $50,000,

along with imprisonment and seizure of the vessel.

The captain of the Atlantic Queen

and Kennedy of the Blue Ocean Society reported the incident to

the authorities, and in mid-September, National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration investigators found the boat driver in violation

of the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The driver was charged an

$8,500 fine, and had 30 days from the notice of the charge to

contest it, work with the attorneys to come up with a different

amount, or pay the whole fine.

The whale has not been seen since

the strike. Right now no one can be sure of its condition, but

Blue Ocean does sometimes observe whales with scars.

Updates on the case and news

on the whale’s condition can be found at the Blue Ocean Society.

Cathy Coletti is assistant

editor of the Gulf of Maine Times.

|

Spotlight

on fin whales

Fin whales

are the second-largest species ever to live on the Earth. They

are 60 feet to 70 feet (18 meters to 21 meters) long on average.

The largest one measured was a female that was longer than 80

feet or 24 meters. They weigh 40 tons to 50 tons (about the weight

of 12 elephants put together). Although they are an endangered

species, Blue Ocean Society in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, sees

them on about 80 percent of its whale watch trips.

SOURCE:

Blue Ocean Society

|

|

![]()